$\newcommand\dom{\text{dom}}

\newcommand\ran{\text{ran}}

\newcommand\restrict{\upharpoonright}$

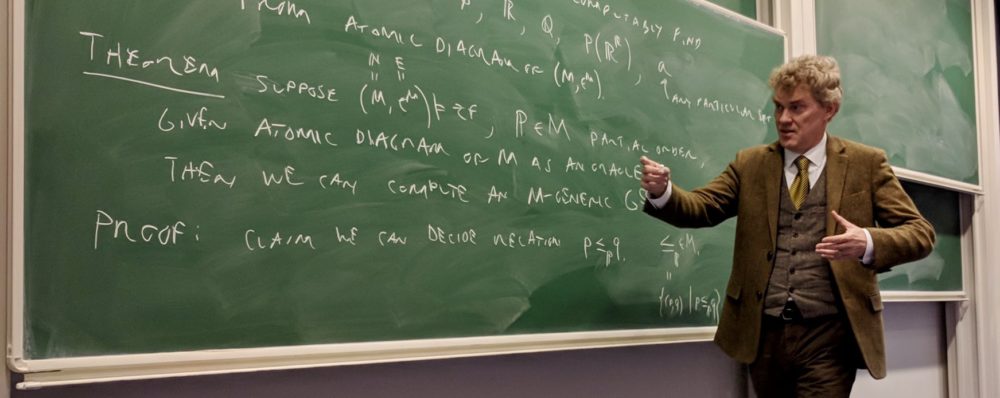

At the Midwest PhilMath Workshop this past weekend, I heard Benjamin Rin (UC Irvine) speak on transfinite recursion, with an interesting new perspective. His idea was to consider transfinite recursion as a basic principle in set theory, along with its close relatives, and see how they relate to the other axioms of set theory, such as the replacement axiom. In particular, he had the idea of using our intuitions about the legitimacy of transfinite computational processes as providing a philosophical foundation for the replacement axiom.

At the Midwest PhilMath Workshop this past weekend, I heard Benjamin Rin (UC Irvine) speak on transfinite recursion, with an interesting new perspective. His idea was to consider transfinite recursion as a basic principle in set theory, along with its close relatives, and see how they relate to the other axioms of set theory, such as the replacement axiom. In particular, he had the idea of using our intuitions about the legitimacy of transfinite computational processes as providing a philosophical foundation for the replacement axiom.

This post is based on what I learned about Rin’s work from his talk at the workshop and in our subsequent conversations there about it. Meanwhile, his paper is now available online:

Benjamin Rin, Transfinite recursion and the iterative conception of set, Synthese, October, 2014, p. 1-26. (preprint).

Since I have a little different perspective on the proposal than Rin did, I thought I would like to explain here how I look upon it. Everything I say here is inspired by Rin’s work.

To begin, I propose that we consider the following axiom, asserting that we may undertake a transfinite recursive procedure along any given well-ordering.

The Principle of Transfinite Recursion. If $A$ is any set with well-ordering $<$ and $F:V\to V$ is any class function, then there is a function $s:A\to V$ such that $s(b)=F(s\upharpoonright b)$ for all $b\in A$, where $s\upharpoonright b$ denotes the function $\langle s(a)\mid a<b\rangle$.

We may understand this principle as an infinite scheme of statements in the first-order language of set theory, where we make separate assertions for each possible first-order formula defining the class function $F$, allowing parameters. It seems natural to consider the principle in the background theory of first-order Zermelo set theory Z, or the Zermelo theory ZC, which includes the axiom of choice, and in each case let me also include the axiom of foundation, which apparently is not usually included in Z. (Alternatively, it is also natural to consider the principle as a single second-order statement, if one wants to work in second-order set theory.)

Theorem. (ZC) The principle of transfinite recursion is equivalent to the axiom of replacement. In other words,

ZC + transfinite recursion = ZFC.

Proof. Work in the Zermelo set theory ZC. The converse implication amounts to the well-known observation in ZF that transfinite recursion is legitimate. Let us quickly sketch the argument. Suppose we are given an instance of transfinite recursion, namely, a well-ordering $\langle A,<\rangle$ and a class function $F:V\to

V$. I claim that for every $b\in A$, there is a unique function $s:\{a\in A\mid a\leq b\}\to V$ obeying the recursive rule $s(d)=F(s\upharpoonright d)$ for all $d\leq b$. The reason is that there can be no least $b$ without such a unique function. If all $a<b$ have such a unique function, then by uniqueness they must cohere with one another, since any difference would show up at a least stage and thereby violate the recursion rule, and so by the replacement axiom of ZFC we may assemble these smaller functions into a single function $t$ defined on all $a<b$, and satisfying the recursion rule for those values. We may then extend this function $t$ to be defined on $b$ itself, simply by defining $u(b)=F(t)$ and $u\upharpoonright b=t$, which thereby satisfies the recursion at $b$. Uniqueness again follows from the fact that there can be no least place of disagreement. Finally, using replacement again, let $s(b)$ be the unique value that arises at $b$ during the recursions that work up to and including $b$, and this function $s:A\to V$ satisfies the recursive definition.

Conversely, assume the Zermelo theory ZC plus the principle of transfinite recursion, and suppose that we are faced with an instance of the replacement axiom. That is, we have a set $A$ and a formula $\varphi$, where every $b\in A$ has a unique $y$ such that $\varphi(b,y)$. By the axiom of choice, there is a well-ordering $<$ of the set $A$. We shall now define the function $F:V\to V$. Given a function $s$, where $\dom(s)=\{a\in A\mid a<b\}$ for some $b\in A$, let $F(s)=y$ be the unique $y$ such that $\varphi(b,y)$; and otherwise let $F(s)$ be anything you like. By the principle of transfinite recursion, there is a function $s:A\to V$ such that $s(b)=F(s\upharpoonright b)$ for every $b\in A$. In this case, it follows that $s(b)$ is the unique $y$ such that $\varphi(a,b)$. Thus, since $s$ is a set, it follows in ZC that $\ran(s)$ is a set, and so we’ve got the image of $A$ under $\varphi$ as a set, which verifies replacement. QED

In particular, it follows that the principle of transfinite recursion implies that every well-ordering is isomorphic to a von Neumann ordinal, a principle Rin refers to as ordinal abstraction. One can see this as a consequence of the previous theorem, since ordinal abstraction holds in ZF by Mostowski’s theorem, which for any well-order $\langle A,<\rangle$ assigns an ordinal to each node $a\mapsto \alpha_a$ according to the recursive rule $\alpha_a=\{\alpha_b\mid b<a\}$. But one can also argue directly as follows, without using the axiom of choice. Assume Z and the principle of transfinite recursion. Suppose that $\langle A,<\rangle$ is a well-ordering. Define the class function $F:V\to V$ so that $F(s)=\ran(s)$, whenever $s$ is a function. By the principle of transfinite recursion, there is a function $s:A\to V$ such that $s(b)=F(s\restrict b)=\ran(s\restrict b)$. One can now simply prove by induction that $s(b)$ is an ordinal and $s$ is an isomorphism of $\langle A,<\rangle$ with $\ran(s)$, which is an ordinal.

Let me remark that the principle of transfinite recursion allows us also to perform proper-class length recursions.

Observation. Assume Zermelo set theory Z plus the principle of transfinite recursion. If $A$ is any particular class with $<$ a set-like well-ordering of $A$ and $F:V\to V$ is any class function, then there is a class function $S:A\to V$ such that $S(b)=F(S\upharpoonright b)$ for every $b\in A$.

Proof. Since $\langle A,<\rangle$ is set-like, the initial segment $A\upharpoonright d=\{a\in A\mid a<d\}$, for any particular $d\in A$, is a set. It follows that the principle of transfinite recursion shows that there is a function $s_d:(A\upharpoonright d)\to V$ such that $s_d(b)=F(s_d\upharpoonright b)$ for every $b<d$. It is now easy to prove by induction that these $s_d$ must all cohere with one another, and so we may define the class $S(b)=s_d(b)$ for any $d$ above $b$ in $A$. (We may assume without loss that $A$ has no largest element, for otherwise it would be a set.) This provides a class function $S:A\to V$ satisfying the recursive definition as desired. QED

Although it appears explicitly as a second-order statement “there is a class function $S$…”, we may actually take this observation as a first-order theorem scheme, if we simply strengthen the conclusion to provide the explicit definition of $S$ that the proof provides. That is, the proof shows exactly how to define $S$, and if we make the observation state that that particular definition works, then what we have is a first-order theorem scheme. So any first-order definition of $A$ and $F$ from parameters leads uniformly to a first-order definition of $S$ using the same parameters.

Thus, using the principle of transfinite recursion, we may also take proper class length transfinite recursions, using any set-like well-ordered class that we happen to have available.

Let us now consider a weakening of the principle of transfinite recursion, where we do not use arbitrary well-orderings, but only the von Neumann ordinals themselves.

Principle of transfinite recursion on ordinals. If $F:V\to V$ is any class function, then for any ordinal $\gamma$ there is a function $s:\gamma\to V$ such that $s(\beta)=F(s\upharpoonright\beta)$ for all $\beta<\gamma$.

This is a weakening of the principle of transfinite recursion, since every ordinal is well-ordered, but in Zermelo set theory, not every well-ordering is necessarily isomorphic to an ordinal. Nevertheless, in the presence of ordinal abstraction, then this ordinal version of transfinite recursion is clearly equivalent to the full principle of transfinite recursion.

Observation. Work in Z. If every well-ordering is isomorphic to an ordinal, then the principle of transfinite recursion is equivalent to its restriction to ordinals.

Meanwhile, let me observe that in general, one may not recover the full principle of transfinite recursion from the weaker principle, where one uses it only on ordinals.

Theorem. (ZFC) The structure $\langle V_{\omega_1},\in\rangle$ satisfies Zermelo set theory ZC with the axiom of choice, but does not satisfy the principle of transfinite recursion. Nevertheless, it does satisfy the principle of transfinite recursion on ordinals.

Proof. It is easy to verify all the Zermelo axioms in $V_{\omega_1}$, as well as the axiom of choice, provided choice holds in $V$. Notice that there are comparatively few ordinals in $V_{\omega_1}$—only the countable ordinals exist there—but $V_{\omega_1}$ has much larger well-orderings. For example, one may find a well-ordering of the reals already in $V_{\omega+k}$ for small finite $k$, and well-orderings of much larger sets in $V_{\omega^2+17}$ and so on as one ascends toward $V_{\omega_1}$. So $V_{\omega_1}$ does not satisfy the ordinal abstraction principle and so cannot satisfy replacement or the principle of transfinite recursion. But I claim nevertheless that it does satisfy the weaker principle of transfinite recursion on ordinals, because if $F:V_{\omega_1}\to V_{\omega_1}$ is any class in this structure, and $\gamma$ is any ordinal, then we may define by recursion in $V$ the function $s(\beta)=F(s\restrict\beta)$, which gives a class $s:\omega_1\to V_{\omega_1}$ that is amenable in $V_{\omega_1}$. In particular, $s\restrict\gamma\in V_{\omega_1}$ for any $\gamma<\omega_1$, simply because $\gamma$ is countable and $\omega_1$ is regular. QED

My view is that this example shows that one doesn’t really want to consider the weakened principle of transfinite recursion on ordinals, if one is working in the Zermelo background ZC, simply because there could be comparatively few ordinals, and this imposes an essentially arbitrary limitation on the principle.

Let me point out, however, that there was a reason we had to go to $V_{\omega_1}$, rather than considering $V_{\omega+\omega}$, which is a more-often mentioned model of the Zermelo axioms. It is not difficult to see that $V_{\omega+\omega}$ does not satisfy the principle of transfinite recursion on the ordinals, because one can define the function $s(n)=\omega+n$ by recursion, setting $s(0)=\omega$ and $s(n+1)=s(n)+1$, but this function does not exist in $V_{\omega+\omega}$. This feature can be generalized as follows:

Theorem. Work in the Zermelo set theory Z. The principle of transfinite recursion on ordinals implies that if $\langle A,<\rangle$ is a well-ordered set, and $A$ is bijective with some ordinal, then $\langle A,<\rangle$ is order-isomorphic with an ordinal.

In other words, we get ordinal abstraction for well-orderings whose underlying set is bijective with an ordinal.

First, the proof of the first theorem above actually shows the following local version:

Lemma. (Z) If one has the principle of transfinite recursion with respect to a well-ordering $\langle A,<\rangle$, then $A$-replacement holds, meaning that if $F:V\to V$ is any class function, then the image $F”A$ is a set.

Proof of theorem. Suppose that $\langle A,<\rangle$ is a well-ordering, and that $A$ is bijective with some ordinal $\kappa$, and that $F:V\to V$ is a class function. Assume the principle of transfinite recursion for $\kappa$. We prove by induction on $d\in A$ that there is a unique function $s_d$ with $\dom(s)=\{a\in A\mid a\leq d\}$ and satisfying the recursive rule $s(b)=F(s\upharpoonright b)$. If this statement is true for all $d<d’$, then because the size of the predecessors of $d’$ in $\langle A,<\rangle$ is at most $\kappa$, we may by the lemma form the set $\{s_d\mid d<d’\}$, which is a set by $\kappa$-replacement. These functions cohere, and the union of these functions gives a function $t:(A\upharpoonright d’)\to V$ satisfying the recursion rule for $F$. Now extend this function one more step by defining $s(d’)=F(t)$ and $s\upharpoonright d’=t$, thereby handling the existence claim at $d’$. As in the main theorem, all these functions cohere with one another, and by $\kappa$-replacement we may form the set $\{s_d\mid d\in A\}$, whose union is the desired function $s:A\to V$ satisfying the recursion rule given by $F$, as desired. QED

For example, if you have the principle of transfinite recursion for ordinals, and $\omega$ exists, then every countable well-ordering is isomorphic to an ordinal. This explains why we had to go to $\omega_1$ to find a model satisfying transfinite recursion on ordinals. One can understand the previous theorem as showing that although the principle of transfinite recursion on ordinals does not prove ordinal abstraction, it does prove many instances of it: for every ordinal $\kappa$, every well-ordering of cardinality at most $\kappa$ is isomorphic to an ordinal.

It is natural also to consider the principle of transfinite recursion along a well-founded relation, rather than merely a well-ordered relation.

The principle of well-founded recursion. If $\langle A,\lhd\rangle$ is a well-founded relation and $F:V\to V$ is any class function, then there is a function $s:A\to V$ such that $s(b)=F(s\restrict b)$ for all $b\in A$, where $s\restrict b$ means the function $s$ restricted to the domain of elements $a\in A$ that are hereditarily below $b$ with respect to $\lhd$.

Although this principle may seem more powerful, in fact it is equivalent to transfinite recursion.

Theorem. (ZC) The principle of transfinite recursion is equivalent to the principle of well-founded recursion.

Proof. The backward direction is immediate, since well-orders are well-founded. For the forward implication, assume that transfinite recursion is legitimate. It follows by the main theorem above that ZFC holds. In this case, well-founded recursion is legitimate by the familiar arguments. For example, one may prove in ZFC that for every node in the field of the relation, there is a unique solution of the recursion defined up to and including that node, simply because there can be no minimal node without this property. Then, by replacement, one may assemble all these functions together into a global solution. Alternatively, arguing directly from transfinite recursion, one may put an ordinal ranking function for any given well-founded relation $\langle A,\lhd\rangle$, and then prove by induction on this rank that one may construct functions defined up to and including any given rank, that accord with the recursive rule. In this way, one gets the full function $s:A\to V$ satisfying the recursive rule. QED

Finally, let me conclude this post by pointing out how my perspective on this topic differs from the treatment given by Benjamin Rin. I am grateful to him for his idea, which I find extremely interesting, and as I said, everything here is inspired by his work.

One difference is that Rin mainly considered transfinite recursion only on ordinals, rather than with respect to an arbitrary well-ordered relation (but see footnote 17 in his paper). For this reason, he had a greater need to consider whether or not he had sufficient ordinal abstraction in his applications. My perspective is that transfinite recursion, taken as a basic principle, has nothing fundamentally to do with the von Neumann ordinals, but rather has to do with a general process undertaken along any well-order. And the theory seems to work better when one undertakes it that way.

Another difference is that Rin stated his recursion principle as a principle about iterating through all the ordinals, rather than only up to any given ordinal. This made the resulting functions $S:\text{Ord}\to V$ into class-sized objects for him, and moved the whole analysis into the realm of second-order set theory. This is why he was led to prove his main equivalence with replacement in second-order Zermelo set theory. My treatment shows that one may undertake the whole theory in first-order set theory, without losing the class-length iterations, since as I explained above the class-length iterations form classes, definable from the original class functions and well-orders. And given that a completely first-order account is possible, it seems preferable to undertake it that way.

Update. (August 17, 2018) I’ve now realized how to eliminate the need for the axiom of choice in the arguments above. Namely, the main argument above shows that the principle of transfinite recursion implies the principle of well-ordered replacement, meaning the axiom of replacement for instances where the domain set is well-orderable. The point now is that in recent work with Alfredo Roque Freire, I have realized that The principle of well-ordered replacement is equivalent to full replacement over Zermelo set theory with foundation. We may therefore deduce:

Corollary. The principle of transfinite recursion is equivalent to the replacement axiom over Zermelo set theory with foundation.

We do not need the axiom of choice for this.

When you say Zermelo set theory, do you mean with foundation? I thought that normally foundation is not considered part of Z. Related to this, foundation is equivalent to $\in$-induction, if I recall correctly, over Z.

In either case, thanks for posting this nice piece of mathematics!

I had thought it included foundation, but it seems you may be right (and so I shall edit). Please take my discussion as including the foundation axiom, at least when I am considering von Neumann ordinals, which I think have issues if one doesn’t have foundation.

I have now added an explicit mention of foundation, and so in this post by Z and ZC I mean the formulations that include foundation.

The paper also uses ZC to refer to ZFC minus replacement, even though it looks as though the name is widely used to refer to ZFC minus replacement and foundation. Thank you both for this observation.

Hi Joel. This is an interesting post. It reminded me of a section in Levy’s book Basic Set Theory. In section V.1.12 on page 163, there is a short discussion about applications of Zorn’s Lemma eliminating recursion. Combined with your remarks, it makes me wonder if AC or some weaker fragment of it might suffice to eliminate or weaken the strength of replacement in some significant way. If so, it seems that there is an argument which lends itself even more so to the already overwhelming evidence in support of choice as a natural set-theoretic principle. Of course, I’m not sure to what extent Levy’s remarks implicitly use replacement (or even how much equivalence there is between AC and Zorn’s Lemma), but I am curious. Would you be willing to share some of your thoughts on Levy’s brief interlude and their relevance (or not) to this apparently new connection between transfinite recursion and replacement?

I’m glad you like it. (And take a look at Rin’s paper.) I’ll look at Levy, but I’m out of the office now for a bit. The proof of the main implication that recursion implies replacement makes fundamental use of AC, since one needs to well-order the set in order to be set up to apply the recursion in the first place.

Prof. Hamkins: Rin does have a preprint of the article on which he based his talk on. This can be found on his homepage in the research section. This said the article is in the October 2014 edition of Synthese so folks can check there also.

Yes, I believe that you are referring to the same preprint to which I had linked in my post.

It looks like Springer has not yet assigned the paper to a particular issue (it is supposed to appear in an upcoming Special Issue, but for now is just online). So I don’t know that it’s really in “the October 2014 edition”. I’ll delete the word October from my site to avoid confusion.

It does say, “October 2014” on the Spring page, if you click on the link in this post and look at upper left. But that may refer to the online edition only.

Thank you, Joel, for writing this post. I just want to take this chance to say here that I completely agree with both points raised at the end.

Do (should) computational notions lie at the core of our conception of set? Ordinal Turing machines and ITTMs do not take us out of the constructible universe L and transfinite recursion for ZFC holds for any model of ZFC (eg. for ZFC+$2^{\aleph_0}$=$\aleph_2$, transfinite recursion must hold for ${\mathscr P}(\omega))$. If one does, however, wish to base one’s conception of set on such computational notions, are there models of ZFC that closely approximate what happens in ordinary recursion theory for $\omega$?

Is there any way I could edit my previous comment? I think I forgot a $ after (and possibly before) \omega?

Do (should) computational notions lie at the core of our conception of set? Ordinal Turing machines and ITTMs do not take us out of the constructible universe L and transfinite recursion for ZFC holds for any model of ZFC (eg. for ZFC+$2^{\aleph_0}$=$\aleph_2$, transfinite recursion must hold for $mathscr P$($\omega$)). If one does, however, wish to base one’s conception of set on such computational notions, are there models of ZFC that closely approximate what happens in ordinary recursion theory for $\omega$?

This is definitely something to pay attention to.

I’m not sure that I understand your final question, so I won’t comment yet. But the issue of ITTMs and OTMs keeping us in constructible territory, which perhaps some would find unappealing, did occur to me. Some responses might be:

(1) At the least, L provides an improvement upon what we get from, say, the stage theory of Boolos, which doesn’t prove the existence of the Church-Kleene ordinal. Certainly $\omega^{\mathrm{CK}}_1$ is a worse candidate for our universe of sets than L. There are also some people who don’t mind a constructible conception of set, and may even prefer it that way. They might be the minority, but in any case this situation is better than a conception so weak that it doesn’t push us past such low levels of the hierarchy.

(2) Perhaps the computational model(s) could be strengthened in some way, e.g., with oracles or some other new apparatus, that would allow for more sets to exist in the universe beyond those of L. I don’t know right now exactly what this strengthening would look like, but it is plausible on the face of it that such an alternate machine could be defined. I would hope to explore this at some point.

That was supposed to say $V_{\omega^{\mathrm{CK}}_1}$.

What would be interesting to see is how one would define the notion of productive set (class?) using ordinal Turing machines. Would such a definition lead us to believe in the existence of this set (class) as the definition of productive set in ordinary recursion theory leads us to believe in its existence? Also, do there exist universal ordinal Turing machines and if so, can their existence allow us to define via diagonalization non-constructive sets?

One possible strengthening would be to consider recognizability instead of computability, i.e. the existence of a program that identifies the object in question when given in the oracle. This notion is in general not transitive, but one can introduce a rather canonical notion of relativized recognizability and form the transitive closure (which, considering only subsets of $\omega$, in fact turns out to be identical to the set of reals that are recursive in some recognizable real). Already for real numbers, the closure $C$ of $\emptyset$ under relativized recognizability for OTMs with ordinal parameters goes far beyond $L$: If $M_{1}^{\sharp}$ exists, then C coincides with the power set of $\omega$ in $M_{1}$, the mouse for a Woodin cardinal. (A preprint showing this should soon be available on Arxiv; meanwhile, here are some notes by Schindler taken during a talk by Schlicht about this: http://wwwmath.uni-muenster.de/logik/Personen/rds/MM3_Schlicht.pdf.) Of course, this is a kind of paradigmatical shift from idealized `construction’ to idealized `observation’ and may quite not be what you want.

Does it make sense to add transfinite recursion to very weak set theories like Adjunctive Set Theory ($A$$S$), if one defines transfinite recursion as being ‘up to any given ordinal’? (Hope this is not too vague–apologies if it is…I am thinking along the lines of adding transfinite induction to primitive recursive arithmetic.) If it does, what theorems could one derive in $A$$S$ $+$ ‘Transfinite Recursion’? In particular, is the inductive set $\omega$ definable in $A$$S$ $+$ ‘Transfinite Recursion’? (Probably not, but if not, it would be to see why not….)

I think you cannot prove that $\omega$ exists in AS plus transfinite recursion, because the principle of transfinite recursion is true in the universe HF of hereditarily finite sets, which has only finite ordinals. It is true there because finite-length recursions will result in finite sets in that universe.

er…it would be nice to see why not….sorry

Very helpful–thanks. It just seems odd to me (and probably only to me) that one must assume outright (as an axiom) the existence of an inductive set for an inductive set to exist. It would be nice if the rules of the ‘formula game’ (in this case, $ZFC$ with Infinity dropped $+$ “some unknown other axioms”–perhaps $A$$S$ was too weak a ‘formula game’) would allow one to ‘construct’ (from the bottom up) the inductive set that the Axiom of Infinity assumes (as Dedekind, for example, hoped….).

Pingback: Second-order transfinite recursion is equivalent to Kelley-Morse set theory over GBC | Joel David Hamkins

Pingback: Replacement for well-ordered sets is equivalent to full replacement over Zermelo + foundation | Joel David Hamkins