[bibtex key=HamkinsYang:SatisfactionIsNotAbsolute]

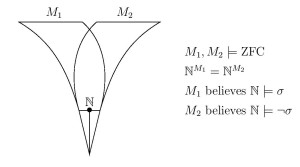

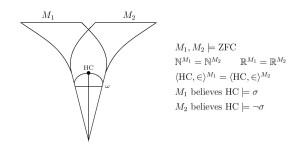

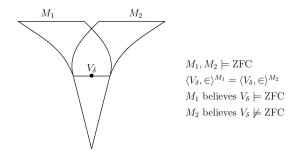

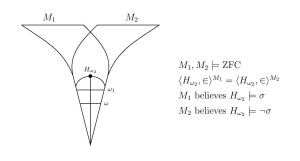

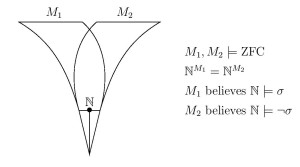

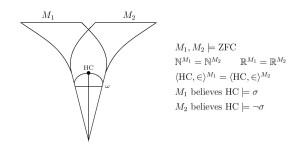

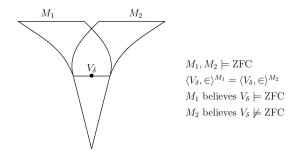

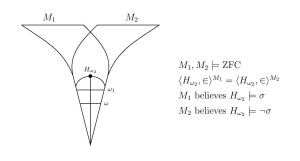

Abstract. We prove that the satisfaction relation of first-order logic is not absolute between models of set theory having the structure and the formulas all in common. Two models of set theory can have the same natural numbers, for example, and the same standard model of arithmetic , yet disagree on their theories of arithmetic truth; two models of set theory can have the same natural numbers and the same arithmetic truths, yet disagree on their truths-about-truth, at any desired level of the iterated truth-predicate hierarchy; two models of set theory can have the same natural numbers and the same reals, yet disagree on projective truth; two models of set theory can have the same or the same rank-initial segment , yet disagree on which assertions are true in these structures.

On the basis of these mathematical results, we argue that a philosophical commitment to the determinateness of the theory of truth for a structure cannot be seen as a consequence solely of the determinateness of the structure in which that truth resides. The determinate nature of arithmetic truth, for example, is not a consequence of the determinate nature of the arithmetic structure itself, but rather, we argue, is an additional higher-order commitment requiring its own analysis and justification.

Many mathematicians and philosophers regard the natural numbers , along with their usual arithmetic structure, as having a privileged mathematical existence, a Platonic realm in which assertions have definite, absolute truth values, independently of our ability to prove or discover them. Although there are some arithmetic assertions that we can neither prove nor refute—such as the consistency of the background theory in which we undertake our proofs—the view is that nevertheless there is a fact of the matter about whether any such arithmetic statement is true or false in the intended interpretation. The definite nature of arithmetic truth is often seen as a consequence of the definiteness of the structure of arithmetic itself, for if the natural numbers exist in a clear and distinct totality in a way that is unambiguous and absolute, then (on this view) the first-order theory of truth residing in that structure—arithmetic truth—is similarly clear and distinct.

Many mathematicians and philosophers regard the natural numbers , along with their usual arithmetic structure, as having a privileged mathematical existence, a Platonic realm in which assertions have definite, absolute truth values, independently of our ability to prove or discover them. Although there are some arithmetic assertions that we can neither prove nor refute—such as the consistency of the background theory in which we undertake our proofs—the view is that nevertheless there is a fact of the matter about whether any such arithmetic statement is true or false in the intended interpretation. The definite nature of arithmetic truth is often seen as a consequence of the definiteness of the structure of arithmetic itself, for if the natural numbers exist in a clear and distinct totality in a way that is unambiguous and absolute, then (on this view) the first-order theory of truth residing in that structure—arithmetic truth—is similarly clear and distinct.

Feferman provides an instance of this perspective when he writes (Feferman 2013, Comments for EFI Workshop, p. 6-7) :

In my view, the conception [of the bare structure of the natural numbers] is completely clear, and thence all arithmetical statements are definite.

It is Feferman’s `thence’ to which we call attention. Martin makes a similar point (Martin, 2012, Completeness or incompleteness of basic mathematical concepts):

What I am suggesting is that the real reason for confidence in first-order completeness is our confidence in the full determinateness of the concept of the natural numbers.

Many mathematicians and philosophers seem to share this perspective. The truth of an arithmetic statement, to be sure, does seem to depend entirely on the structure , with all quantifiers restricted to and using only those arithmetic operations and relations, and so if that structure has a definite nature, then it would seem that the truth of the statement should be similarly definite.

Nevertheless, in this article we should like to tease apart these two ontological commitments, arguing that the definiteness of truth for a given mathematical structure, such as the natural numbers, the reals or higher-order structures such as or , does not follow from the definite nature of the underlying structure in which that truth resides. Rather, we argue that the commitment to a theory of truth for a structure is a higher-order ontological commitment, going strictly beyond the commitment to a definite nature for the underlying structure itself.

Nevertheless, in this article we should like to tease apart these two ontological commitments, arguing that the definiteness of truth for a given mathematical structure, such as the natural numbers, the reals or higher-order structures such as or , does not follow from the definite nature of the underlying structure in which that truth resides. Rather, we argue that the commitment to a theory of truth for a structure is a higher-order ontological commitment, going strictly beyond the commitment to a definite nature for the underlying structure itself.

We make our argument in part by proving that different models of set theory can have a structure identically in common, even the natural numbers, yet disagree on the theory of truth for that structure.

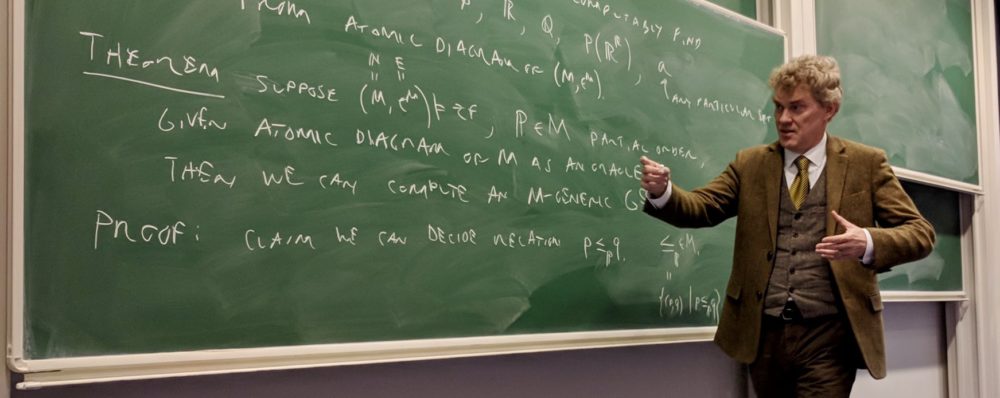

Theorem.

- Two models of set theory can have the same structure of arithmetic yet disagree on the theory of arithmetic truth.

- Two models of set theory can have the same natural numbers and a computable linear order in common, yet disagree about whether it is a well-order.

- Two models of set theory that have the same natural numbers and the same reals, yet disagree on projective truth.

- Two models of set theory can have a transitive rank initial segment in common yet disagree about whether it is a model of ZFC.

The proofs use only elementary classical methods, and might be considered to be a part of the folklore of the subject of models of arithmetic. The paper includes many further examples of the phenomenon, and concludes with a philosophical discussion of the issue of definiteness, concerning the question of whether one may deduce definiteness-of-truth from definiteness-of-objects and definiteness-of-structure.

The proofs use only elementary classical methods, and might be considered to be a part of the folklore of the subject of models of arithmetic. The paper includes many further examples of the phenomenon, and concludes with a philosophical discussion of the issue of definiteness, concerning the question of whether one may deduce definiteness-of-truth from definiteness-of-objects and definiteness-of-structure.

This will be a talk for specialists in philosophy, mathematics and the philosophy of mathematics, given as part of the workshop

This will be a talk for specialists in philosophy, mathematics and the philosophy of mathematics, given as part of the workshop