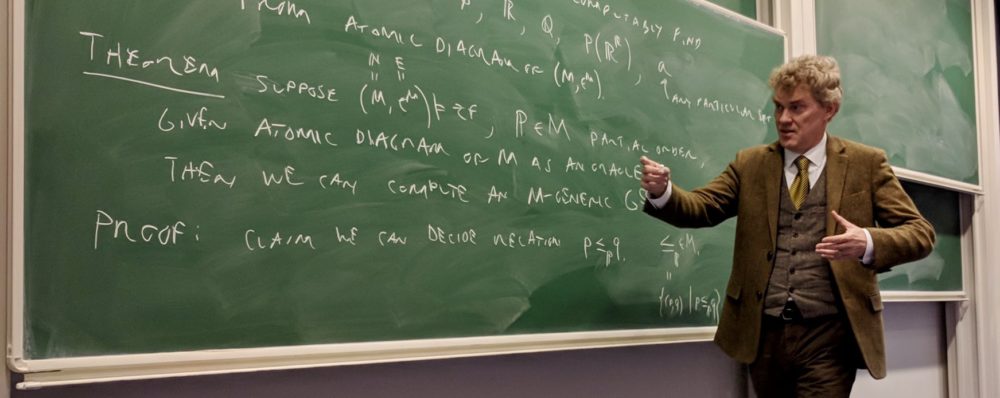

I am honored to be giving the 2025 William Reinhardt Memorial Lecture at the University of Colorado Boulder, March 11, 2025.

How we might have taken the Continuum Hypothesis as a fundamental axiom, necessary for mathematics

Abstract. I shall describe a simple historical thought experiment showing how our attitude toward the continuum hypothesis might easily have been very different than it is. If our mathematical history had been just a little different, I claim, if certain mathematical discoveries had been made in a slightly different order, then we would naturally have come to view the continuum hypothesis as a fundamental axiom of set theory, necessary for mathematics, indispensable even for the core ideas of calculus.

Reversing this idea: what current axioms do we have that might have been otherwise if mathematics had historically developed differently?

Yes, that is an interesting question, and fits in with my larger theme: to argue for contingency in what counts as a fundamental axiom in mathematics. This is, after all, a pluralist point of view.

I agree, but I really want to know if you have any candidates.

The axiom of choice is the obvious one, but it has no concrete consequences. I can think of alternative history leading to axioms that contradict the axiom of infinity or cutting V off at some higher rank, but I can’t think of any that could lead to arithmetical consequences contradicting ZF. The closest I can come is the axiom that V=M, where M is the “strongly constructible sets” defined in Cohen’s book—this axiom is equivalent to V=L plus the denial of SM (no standard set models for ZF). The path to such an axiom would be the conviction that only those sets exist that explicitly must exist, arising from distaste for nonconstructive or nondefinable pathologies. But that’s consistent with ZFC, it’s an axiomatizable subset of the theory of the Shepherdson minimal model!

(Denying AxInf is more “concrete” than V=M and contradicts ZF, but in an uninteresting way because it doesn’t give us anything new that is true about finite sets and its new consequences in set theory are trivial, while V=M has all the consequences of V=L and more.)

The only alternative history I can think of that is more productive of arithmetical consequences than “V=M” is the one that gives a real valued measure on the continuum, because that implies consistency of all cardinals below a measurable, as well as other concrete low level statements.

But I still can’t think of an alternative history that would contradict ZF about arithmetic, except by using some kind of paraconsistent logic that allows ultrafinitist statements like “the powerset function is not total” (or, if that’s too radical, that the towerset function taking n to an exponential stack of n 2’s is not total, or, if that’s still too radical, the denial of the totality of Ackermann’s function).

Maybe that last one is the answer? Accept PRA but deny Ackermann? Or accept PA but deny Goodstein? Unlike denying powerset or towerset, this allows the smooth development of much of ordinary mathematics.

It remains to be explained what kind of historical development would lead to actually denying the Ackerman or Goodstein theorems, rather than just refusing to accept axioms that prove them; perhaps something physics-based? EFA is weaker than PRA and does not suffice for things like the VanDerWaerden and Hales-Jewett theorems, which need not only the Tower function to be total but also the next level Supertower function (Shelah showed that was enough, you don’t need all of PRA).

Correction! Gowers found a finite stack of 2’s upper bound for Van Der Waerden, so EFA is probably enough, but Hales-Jewett still seems to need supertowers in all known upper bounds. The best lower bounds for H-J are still only exponential, though, so maybe EFA is enough after all…