[bibtex key=EvansHamkins2014:TransfiniteGameValuesInInfiniteChess]

In this article, C. D. A. Evans and I investigate the transfinite game values arising in infinite chess, providing both upper and lower bounds on the supremum of these values—the omega one of chess—denoted by $\omega_1^{\mathfrak{Ch}}$ in the context of finite positions and by $\omega_1^{\mathfrak{Ch}_{\!\!\!\!\sim}}$ in the context of all positions, including those with infinitely many pieces. For lower bounds, we present specific positions with transfinite game values of $\omega$, $\omega^2$, $\omega^2\cdot k$ and $\omega^3$. By embedding trees into chess, we show that there is a computable infinite chess position that is a win for white if the players are required to play according to a deterministic computable strategy, but which is a draw without that restriction. Finally, we prove that every countable ordinal arises as the game value of a position in infinite three-dimensional chess, and consequently the omega one of infinite three-dimensional chess is as large as it can be, namely, true $\omega_1$.

The article is 38 pages, with 18 figures detailing many interesting positions of infinite chess. My co-author Cory Evans holds the chess title of U.S. National Master.

Wästlund’s MathOverflow question | My answer there

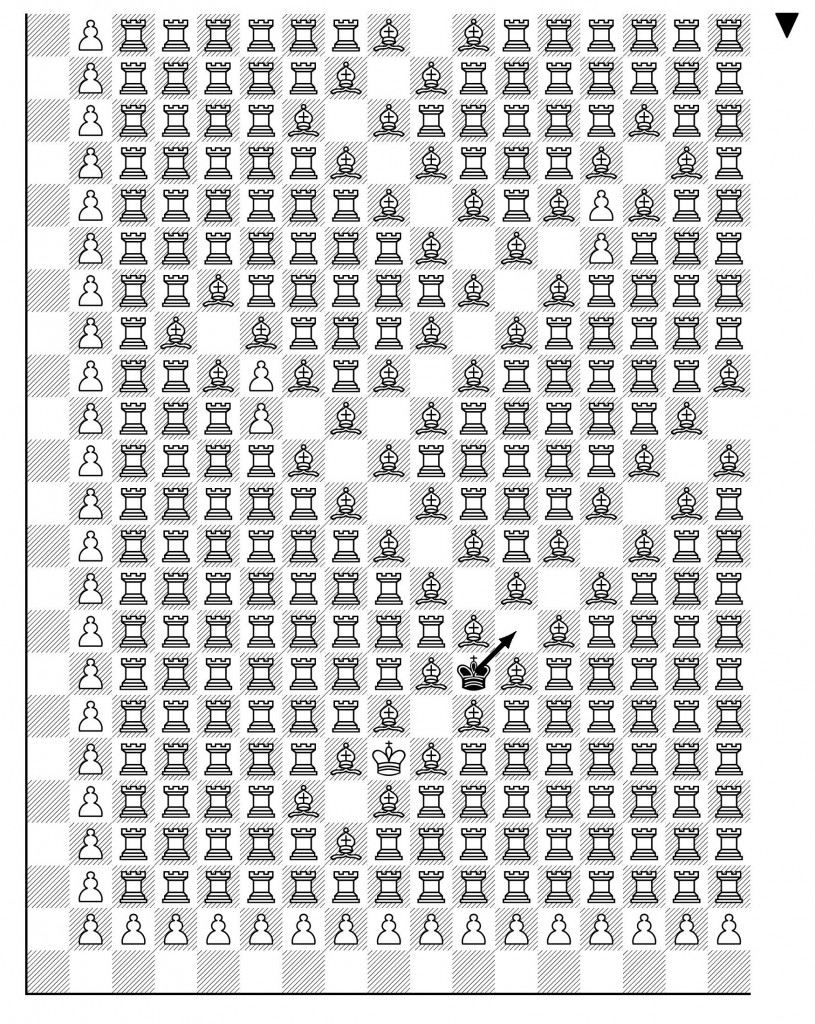

Let’s display here a few of the interesting positions.

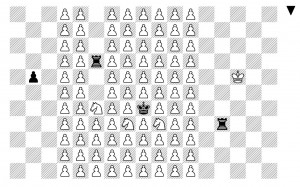

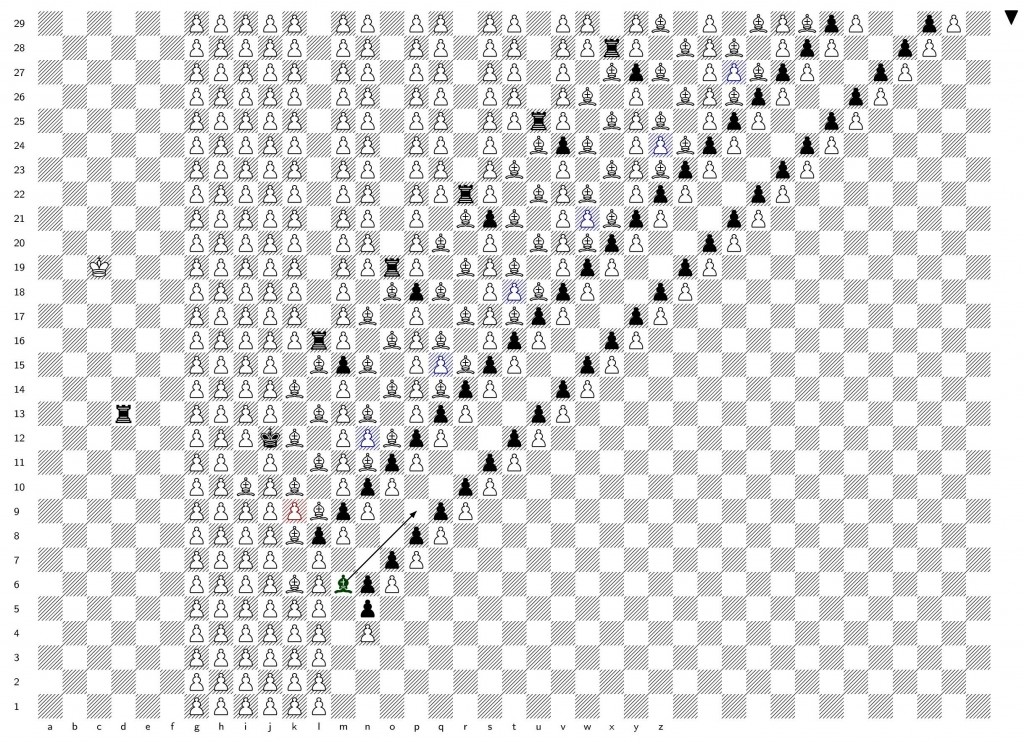

First, a simple new position with value $\omega$. The main line of play here calls for black to move his center rook up to arbitrary height, and then white slowly rolls the king into the rook for checkmate. For example, 1…Re10 2.Rf5+ Ke6 3.Qd5+ Ke7 4.Rf7+ Ke8 5.Qd7+ Ke9 6.Rf9#. By playing the rook higher on the first move, black can force this main line of play have any desired finite length. We have further variations with more black rooks and white king.

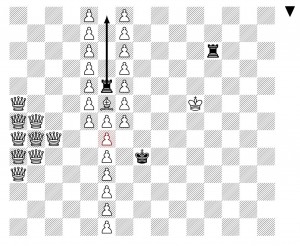

Next, consider an infinite position with value $\omega^2$. The central black rook, currently attacked by a pawn, may be moved up by black arbitrarily high, where it will be captured by a white pawn, which opens a hole in the pawn column. White may systematically advance pawns below this hole in order eventually to free up the pieces at the bottom that release the mating material. But with each white pawn advance, black embarks on an arbitrarily long round of harassing checks on the white king.

Here is a similar position with value $\omega^2$, which we call, “releasing the hordes”, since white aims ultimately to open the portcullis and release the queens into the mating chamber at right. The black rook ascends to arbitrary height, and white aims to advance pawns, but black embarks on arbitrarily long harassing check campaigns to delay each white pawn advance.

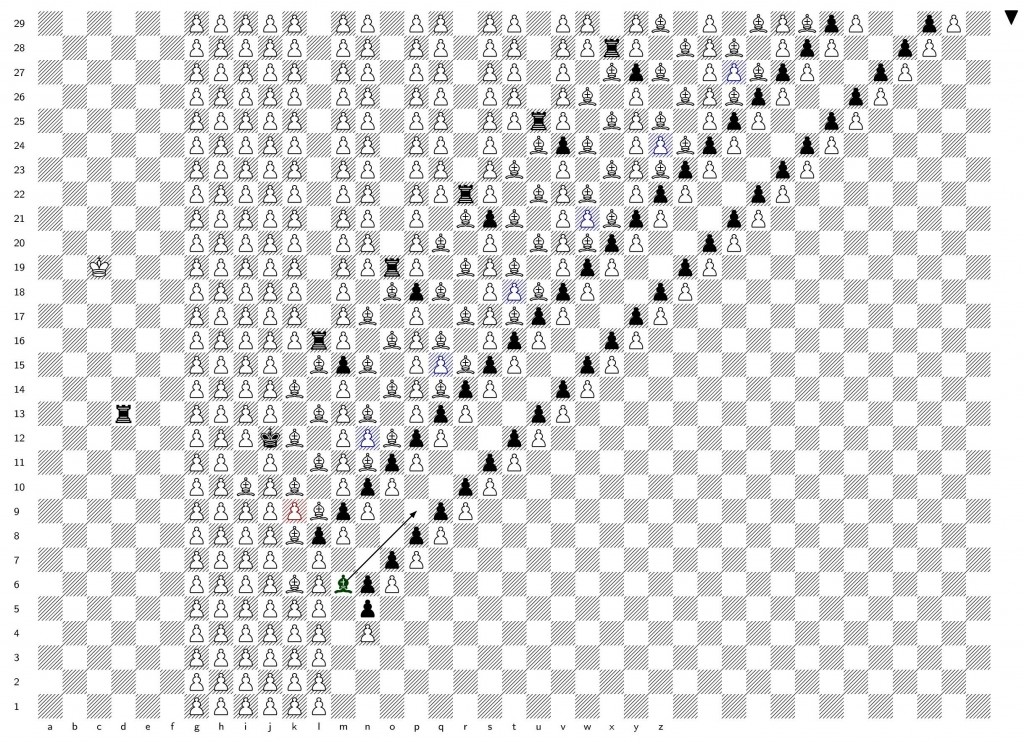

Next, by iterating this idea, we produce a position with value $\omega^2\cdot 4$. We have in effect a series of four such rook towers, where each one must be completed before the next is activated, using the “lock and key” concept explained in the paper.

We can arrange the towers so that black may in effect choose how many rook towers come into play, and thus he can play to a position with value $\omega^2\cdot k$ for any desired $k$, making the position overall have value $\omega^3$.

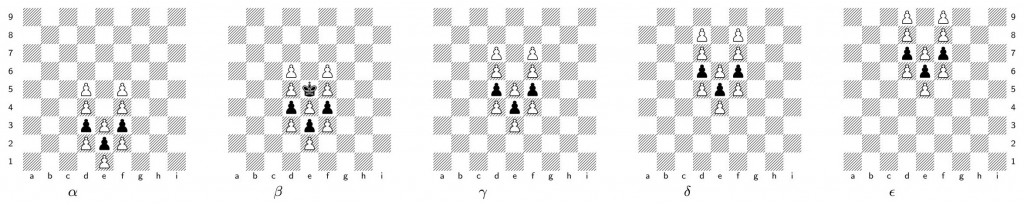

Another interesting thing we noticed is that there is a computable position in infinite chess, such that in the category of computable play, it is a win for white—white has a computable strategy defeating any computable strategy of black—but in the category of arbitrary play, both players have a drawing strategy. Thus, our judgment of whether a position is a win or a draw depends on whether we insist that players play according to a deterministic computable procedure or not.

The basic idea for this is to have a computable tree with no computable infinite branch. When black plays computably, he will inevitably be trapped in a dead-end.

In the paper, we conjecture that the omega one of chess is as large as it can possibly be, namely, the Church-Kleene ordinal $\omega_1^{CK}$ in the context of finite positions, and true $\omega_1$ in the context of all positions.

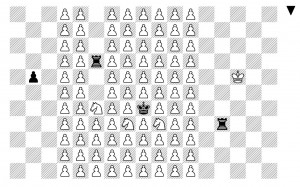

Our idea for proving this conjecture, unfortunately, does not quite fit into two-dimensional chess geometry, but we were able to make the idea work in infinite **three-dimensional** chess. In the last section of the article, we prove:

Theorem. Every countable ordinal arises as the game value of an infinite position of infinite three-dimensional chess. Thus, the omega one of infinite three dimensional chess is as large as it could possibly be, true $\omega_1$.

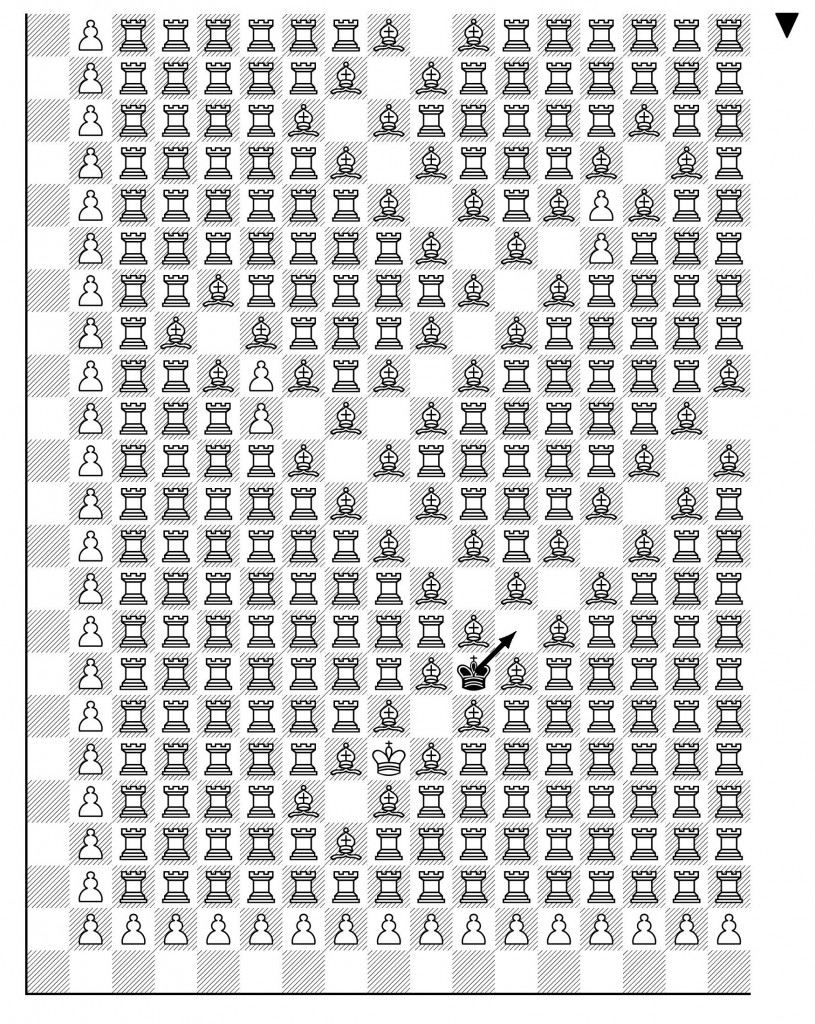

Here is a part of the position. Imagine the layers stacked atop each other, with $\alpha$ at the bottom and further layers below and above. The black king had entered at $\alpha$e4, was checked from below and has just moved to $\beta$e5. Pushing a pawn with check, white continues with 1.$\alpha$e4+ K$\gamma$e6 2.$\beta$e5+ K$\delta$e7 3.$\gamma$e6+ K$\epsilon$e8 4.$\delta$e7+, forcing black to climb the stairs (the pawn advance 1.$\alpha$e4+ was protected by a corresponding pawn below, since black had just been checked at $\alpha$e4).

The overall argument works in higher dimensional chess, as well as three-dimensional chess that has only finite extent in the third dimension $\mathbb{Z}\times\mathbb{Z}\times k$, for $k$ above 25 or so.

![By PeterPan23 [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/f/fb/Darts_in_a_dartboard.jpg)