I was quoted in The Global Math Commons, Simons Foundation, Science News Features article by Erica Klarreich, May 18, 2013, concerning MathOverflow.

In memory, Clark John Hamkins (1930- 2013)

My father, Clark John Hamkins (1930 – 2013) passed away May 11, 2013 at his home in Brunswick, Maine. He was a good man, witty, kind, intelligent, honest, hard-working, caring, curious, patient, philosophical, mathematical, practical, fair. The world has just lost a great human being. He was a loving family man, married to my mother, Monica, for 55 years (their wedding anniversary was yesterday), with six children and thirteen grandchildren.

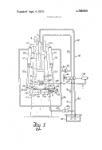

He was an engineer’s engineer, one who could take apart any machine and put it back together and tell you all about the ways in which the design was flawed or how it was clever. I think of his work as a kind of meta-engineering, for he designed the machines for manufacturing a product, bending pipes and twisting wire, rather than the product itself. He held a number of patents for his inventions, including some for his design of a manufacturing apparatus for winding semi-toroidal transformers. When I was a kid, he designed and built in his wood shop a hand-crank centrifugal honey-extractor, which we used to harvest the crop from our bee hives. He taught all his kids their way around a wood shop, how to cut, saw, nail, drill, screw, sand, bore, file, buff, solder, join, plane, dowel, glue, measure, how to use all manner of hand tools and the jig saw, the band saw, the table saw, the mitre saw, the drill press, the belt sander. He was beyond serious, with a lathe in his shop. “Use the right tool for the job,” I can still hear him say, and “measure twice, cut once; measure once, cut twice,” a warning to those who would rush their work. He made all manner of toys for his children and then for his grandchildren. He made cabinets, tools, furniture, items of all kinds, large and small, fine and plain.  He kept and used a wood shop his entire adult life, insisting even in his final days that he go down into it. One of his final projects was to design and build a beautiful, melodious whale-motif dulcimer.

He kept and used a wood shop his entire adult life, insisting even in his final days that he go down into it. One of his final projects was to design and build a beautiful, melodious whale-motif dulcimer.

He was an artist, and as a young man produced oil paintings, which move me to this day. Long ago, before having kids, he made architectural drawings for the family home he had planned, and it is clear in retrospect that he hadn’t planned at that time on having such a large family. (The joke in our family is that Dad wanted four kids and Mom wanted two, and they both got their wish!) Later, he would inevitably win our family games of pictionary, where one is given the task to draw the meaning of a word selected randomly from the dictionary. His drawings always started with a clear simple line, capturing the essence of the concept, which was then fleshed out in fuller artistic flair until his partner said the word. I found an old math book of his, from his own school days, with a chapter on Polar Coordinates in which he had drawn a wonderful Eskimo, carrying a harpoon and fish, and an igloo.

He was a teacher at heart. He explained the slide rule to me when I was young, and gave a lesson on logarithms and log tables and the accompanying explanation of linear interpolation. He explained to me as a child what $x^2$ and $x^3$ meant, and then, with a twinkle in his eye, as I listened wide-eyed and dumbstruck, about what $x^{2.3}$ meant. Some of my fondest young memories with him include viewings of the moon and planets through a telescope, as I shivered in my pajamas in the cool night air, pondering the craters and drinking hot cocoa. He would discuss the various historical astronomical theories, comparing Copernicus with Ptolemy and the role of Tycho Brahe. He loved a good scientific controversy, and liked even more to figure things out himself. He liked to put a scientific explanation in a historical context.

He was a programmer, programming computers in the earliest days. I brought his cast-off computer cards, punched paper tapes and so on into my third-grade classroom for show-and-tell. I remember him poring over expansive flowcharts spread across the kitchen table in the evenings. He made sure that his kids were learning how to program.

He was a voracious reader, consuming books in science, philosophy, literature, history, archeology, biology, physics, mathematics. You name it; he read it.

He was a skeptic.

He was a rebel physicist, refusing to accept the conclusion of the Michelson-Morley experiment on relativistic length foreshortening and time contraction. And he backed up his beliefs by writing an account of this part of physics, re-developing the theory from an alternative perspective of his own invention, involving a notion of time translation, which avoided the need for those paradoxical conclusions, but ended up deriving the same fundamental equations.

I will miss him.

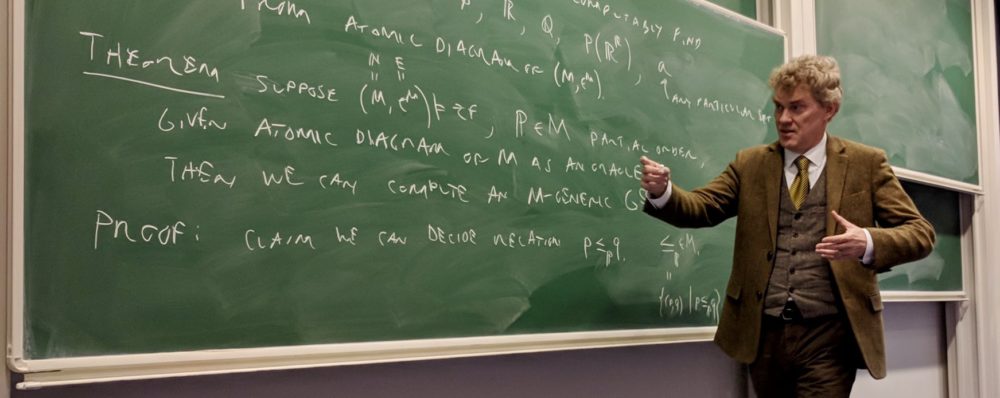

Algebraicity and implicit definability in set theory, CUNY, May 2013

This is a talk May 10, 2013 for the CUNY Set Theory Seminar.

Abstract. An element a is definable in a model M if it is the unique object in M satisfying some first-order property. It is algebraic, in contrast, if it is amongst at most finitely many objects satisfying some first-order property φ, that is, if { b | M satisfies φ[b] } is a finite set containing a. In this talk, I aim to consider the situation that arises when one replaces the use of definability in several parts of set theory with the weaker concept of algebraicity. For example, in place of the class HOD of all hereditarily ordinal-definable sets, I should like to consider the class HOA of all hereditarily ordinal algebraic sets. How do these two classes relate? In place of the study of pointwise definable models of set theory, I should like to consider the pointwise algebraic models of set theory. Are these the same? In place of the constructible universe L, I should like to consider the inner model arising from iterating the algebraic (or implicit) power set operation rather than the definable power set operation. The result is a highly interesting new inner model of ZFC, denoted Imp, whose properties are only now coming to light. Is Imp the same as L? Is it absolute? I shall answer all these questions at the talk, but many others remain open.

This is joint work with Cole Leahy (MIT).

The theory of infinite games, with examples, including infinite chess

This will be a talk on April 30, 2013 for a joint meeting of the Yeshiva University Mathematics Club and the Yeshiva University Philosophy Club. The event will take place in 5:45 pm in Furst Hall, on the corner of Amsterdam Ave. and 185th St.

Abstract. I will give a general introduction to the theory of infinite games, suitable for mathematicians and philosophers. What does it mean to play an infinitely long game? What does it mean to have a winning strategy for such a game? Is there any reason to think that every game should have a winning strategy for one player or another? Could there be a game, such that neither player has a way to force a win? Must every computable game have a computable winning strategy? I will present several game paradoxes and example infinitary games, including an infinitary version of the game of Nim, and several examples from infinite chess.

NYlogic entry | Yeshiva University | Infinite chess | Video

Norman Lewis Perlmutter

Norman Lewis Perlmutter successfully defended his dissertation under my supervision and will earn his Ph.D. at the CUNY Graduate Center in May, 2013. His dissertation consists of two parts. The first chapter arose from the observation that while direct limits of large cardinal embeddings and other embeddings between models of set theory are pervasive in the subject, there is comparatively little study of inverse limits of systems of such embeddings. After such an inverse system had arisen in Norman’s joint work on Generalizations of the Kunen inconsistency, he mounted a thorough investigation of the fundamental theory of these inverse limits. In chapter two, he investigated the large cardinal hierarchy in the vicinity of the high-jump cardinals. During this investigation, he ended up refuting the existence of what are now called the excessively hypercompact cardinals, which had appeared in several published articles. Previous applications of that notion can be made with a weaker notion, what is now called a hypercompact cardinal.

web page | math genealogy | MathSciNet | ar$\chi$iv | related posts

Norman Lewis Perlmutter, “Inverse limits of models of set theory and the large cardinal hierarchy near a high-jump cardinal” Ph.D. dissertation for The Graduate Center of the City University of New York, May, 2013.

Abstract. This dissertation consists of two chapters, each of which investigates a topic in set theory, more specifically in the research area of forcing and large cardinals. The two chapters are independent of each other.

The first chapter analyzes the existence, structure, and preservation by forcing of inverse limits of inverse-directed systems in the category of elementary embeddings and models of set theory. Although direct limits of directed systems in this category are pervasive in the set-theoretic literature, the inverse limits in this same category have seen less study. I have made progress towards fully characterizing the existence and structure of these inverse limits. Some of the most important results are as follows. If the inverse limit exists, then it is given by either the entire thread class or a rank-initial segment of the thread class. Given sufficient large cardinal hypotheses, there are systems with no inverse limit, systems with inverse limit given by the entire thread class, and systems with inverse limit given by a proper subset of the thread class. Inverse limits are preserved in both directions by forcing under fairly general assumptions. Prikry forcing and iterated Prikry forcing are important techniques for constructing some of the examples in this chapter.

The second chapter analyzes the hierarchy of the large cardinals between a supercompact cardinal and an almost-huge cardinal, including in particular high-jump cardinals. I organize the large cardinals in this region by consistency strength and implicational strength. I also prove some results relating high-jump cardinals to forcing. A high-jump cardinal is the critical point of an elementary embedding $j: V \to M$ such that $M$ is closed under sequences of length $\sup\{\ j(f)(\kappa) \mid f: \kappa \to \kappa\ \}$. Two of the most important results in the chapter are as follows. A Vopenka cardinal is equivalent to an Woodin-for-supercompactness cardinal. The existence of an excessively hypercompact cardinal is inconsistent.

Joining the Doctoral Faculty in Philosophy

I am recently informed that I shall be joining the Doctoral Faculty of the Philosophy Program at the CUNY Graduate Center, in addition to my current appointments in Mathematics and in Computer Science. This means I shall now be able to teach graduate courses in philosophy at the Graduate Center and also to supervise Ph.D. dissertations in philosophy there. I am pleased to become a part of the GC Philosophy Program, which is so highly ranked in the area of mathematical logic, and I look forward to making a positive contribution to the program.

Interviewed by Richard Marshall at 3:AM Magazine

I was recently interviewed by Richard Marshall at 3:AM Magazine, which was a lot of fun. You can see that his piece starts out, however, rather over-the-top…

3:AM MAGAZINE

playing infinite chess

Joel David Hamkins interviewed by Richard Marshall.

Joel David Hamkins is a maths/logic hipster, melting the logic/maths hive mind with ideas that stalk the same wild territory as Frege, Tarski, Godel, Turing and Cantor. He thinks we all can go there and that we all should. He gives tips about the Moebius strip to six year olds and plays around with his sons homework. He has discovered all sorts of wonders involving supertasks, infinite-time Turing machines, black-hole computations, the mathematics of the uncountable, the lost melody phenomenon of infintary computability (which really should be the name of a band), set theory and multiverses, infinite utilitarianism, and infinite chess. He’s also thinking about whether we really have an absolute notion of the finite and doubts if any of this is brain melting, which is just a testimony to his modesty. He also thinks that although maths is open to all he thinks mathematicians could use more metaphors and silly terminology to get their ideas across better than they do. All in all, this is the grooviest of the hard core maths/logic groovsters. Bodacious!

→ continue to the rest of the interview

The interview is now available at Marshall’s site 3:16, along with the full collection of his interviews.

Pluralism in mathematics: the multiverse view in set theory and the question of whether every mathematical statement has a definite truth value, Rutgers, March 2013

This is a talk for the Rutgers Logic Seminar on March 25th, 2013. Simon Thomas specifically requested that I give a talk aimed at philosophers.

Abstract. I shall describe the debate on pluralism in the philosophy of set theory, specifically on the question of whether every mathematical and set-theoretic assertion has a definite truth value. A traditional Platonist view in set theory, which I call the universe view, holds that there is an absolute background concept of set and a corresponding absolute background set-theoretic universe in which every set-theoretic assertion has a final, definitive truth value. I shall try to tease apart two often-blurred aspects of this perspective, namely, to separate the claim that the set-theoretic universe has a real mathematical existence from the claim that it is unique. A competing view, the multiverse view, accepts the former claim and rejects the latter, by holding that there are many distinct concepts of set, each instantiated in a corresponding set-theoretic universe, and a corresponding pluralism of set-theoretic truths. After framing the dispute, I shall argue that the multiverse position explains our experience with the enormous diversity of set-theoretic possibility, a phenomenon that is one of the central set-theoretic discoveries of the past fifty years and one which challenges the universe view. In particular, I shall argue that the continuum hypothesis is settled on the multiverse view by our extensive knowledge about how it behaves in the multiverse, and as a result it can no longer be settled in the manner formerly hoped for.

Some of this material arises in my recent articles:

The omega one of chess, CUNY, March, 2013

This is a talk for the New York Set Theory Seminar on March 1, 2013.

This talk will be based on my recent paper with C. D. A. Evans, Transfinite game values in infinite chess.

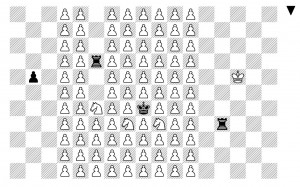

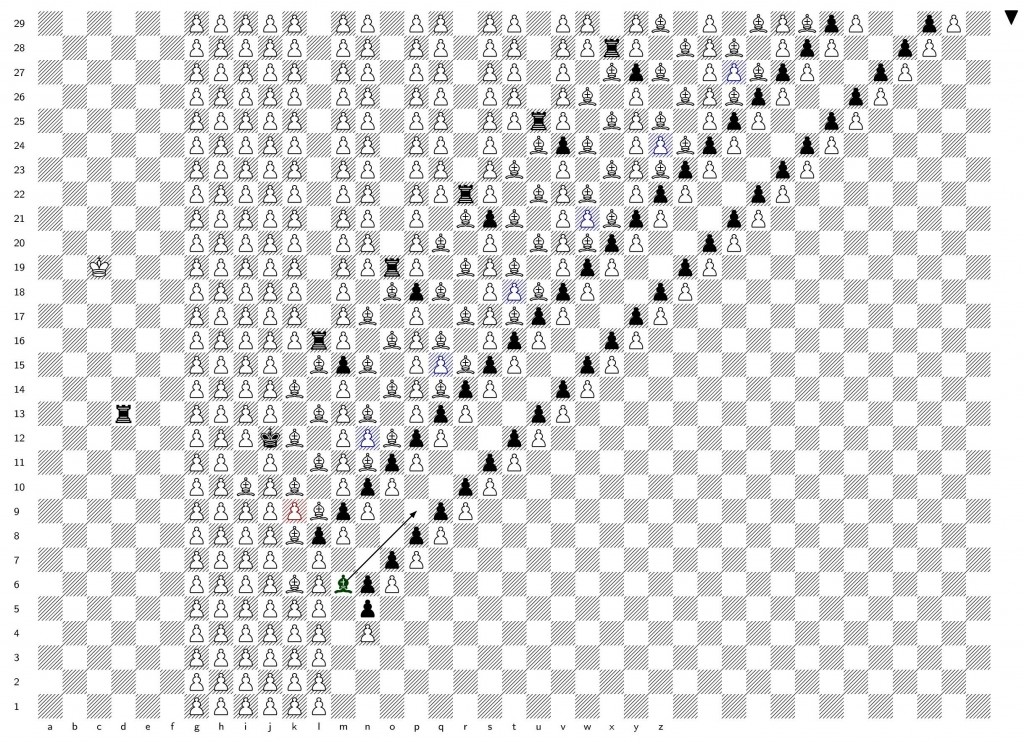

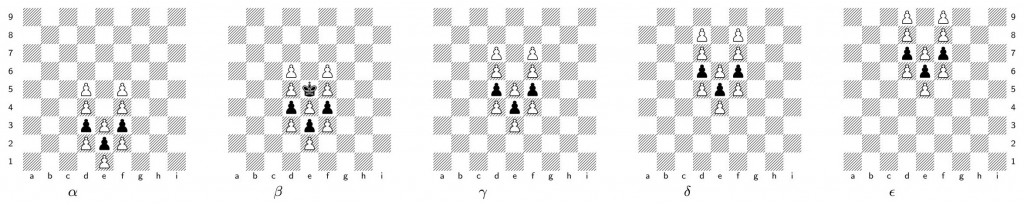

Infinite chess is chess played on an infinite chessboard. Since checkmate, when it occurs, does so after finitely many moves, this is technically what is known as an open game, and is therefore subject to the theory of open games, including the theory of ordinal game values. In this talk, I will give a general introduction to the theory of ordinal game values for ordinal games, before diving into several examples illustrating high transfinite game values in infinite chess. The supremum of these values is the omega one of chess, denoted by $\omega_1^{\mathfrak{Ch}}$ in the context of finite positions and by $\omega_1^{\mathfrak{Ch}_{\hskip-1.5ex {\ \atop\sim}}}$ in the context of all positions, including those with infinitely many pieces. For lower bounds, we have specific positions with transfinite game values of $\omega$, $\omega^2$, $\omega^2\cdot k$ and $\omega^3$. By embedding trees into chess, we show that there is a computable infinite chess position that is a win for white if the players are required to play according to a deterministic computable strategy, but which is a draw without that restriction. Finally, we prove that every countable ordinal arises as the game value of a position in infinite three-dimensional chess, and consequently the omega one of infinite three-dimensional chess is as large as it can be, namely, true $\omega_1$.

Transfinite game values in infinite chess

[bibtex key=EvansHamkins2014:TransfiniteGameValuesInInfiniteChess]

In this article, C. D. A. Evans and I investigate the transfinite game values arising in infinite chess, providing both upper and lower bounds on the supremum of these values—the omega one of chess—denoted by $\omega_1^{\mathfrak{Ch}}$ in the context of finite positions and by $\omega_1^{\mathfrak{Ch}_{\!\!\!\!\sim}}$ in the context of all positions, including those with infinitely many pieces. For lower bounds, we present specific positions with transfinite game values of $\omega$, $\omega^2$, $\omega^2\cdot k$ and $\omega^3$. By embedding trees into chess, we show that there is a computable infinite chess position that is a win for white if the players are required to play according to a deterministic computable strategy, but which is a draw without that restriction. Finally, we prove that every countable ordinal arises as the game value of a position in infinite three-dimensional chess, and consequently the omega one of infinite three-dimensional chess is as large as it can be, namely, true $\omega_1$.

The article is 38 pages, with 18 figures detailing many interesting positions of infinite chess. My co-author Cory Evans holds the chess title of U.S. National Master.

Wästlund’s MathOverflow question | My answer there

Let’s display here a few of the interesting positions.

First, a simple new position with value $\omega$. The main line of play here calls for black to move his center rook up to arbitrary height, and then white slowly rolls the king into the rook for checkmate. For example, 1…Re10 2.Rf5+ Ke6 3.Qd5+ Ke7 4.Rf7+ Ke8 5.Qd7+ Ke9 6.Rf9#. By playing the rook higher on the first move, black can force this main line of play have any desired finite length. We have further variations with more black rooks and white king.

Next, consider an infinite position with value $\omega^2$. The central black rook, currently attacked by a pawn, may be moved up by black arbitrarily high, where it will be captured by a white pawn, which opens a hole in the pawn column. White may systematically advance pawns below this hole in order eventually to free up the pieces at the bottom that release the mating material. But with each white pawn advance, black embarks on an arbitrarily long round of harassing checks on the white king.

Here is a similar position with value $\omega^2$, which we call, “releasing the hordes”, since white aims ultimately to open the portcullis and release the queens into the mating chamber at right. The black rook ascends to arbitrary height, and white aims to advance pawns, but black embarks on arbitrarily long harassing check campaigns to delay each white pawn advance.

Next, by iterating this idea, we produce a position with value $\omega^2\cdot 4$. We have in effect a series of four such rook towers, where each one must be completed before the next is activated, using the “lock and key” concept explained in the paper.

We can arrange the towers so that black may in effect choose how many rook towers come into play, and thus he can play to a position with value $\omega^2\cdot k$ for any desired $k$, making the position overall have value $\omega^3$.

Another interesting thing we noticed is that there is a computable position in infinite chess, such that in the category of computable play, it is a win for white—white has a computable strategy defeating any computable strategy of black—but in the category of arbitrary play, both players have a drawing strategy. Thus, our judgment of whether a position is a win or a draw depends on whether we insist that players play according to a deterministic computable procedure or not.

The basic idea for this is to have a computable tree with no computable infinite branch. When black plays computably, he will inevitably be trapped in a dead-end.

In the paper, we conjecture that the omega one of chess is as large as it can possibly be, namely, the Church-Kleene ordinal $\omega_1^{CK}$ in the context of finite positions, and true $\omega_1$ in the context of all positions.

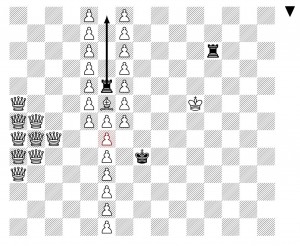

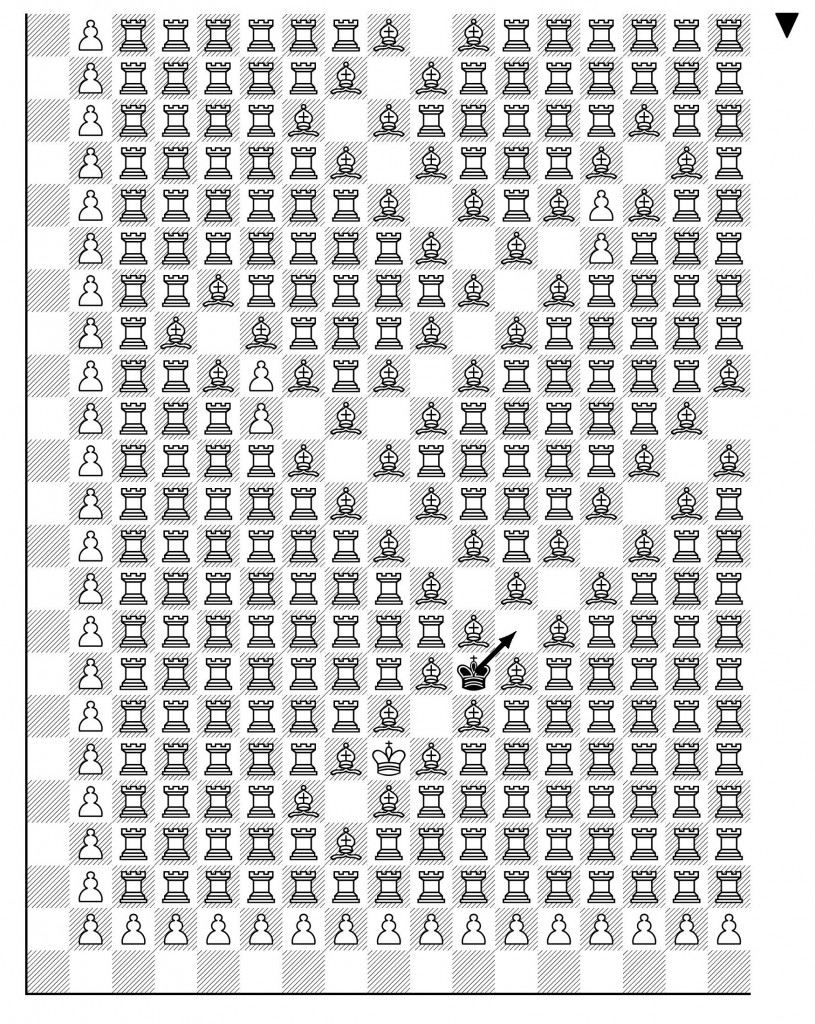

Our idea for proving this conjecture, unfortunately, does not quite fit into two-dimensional chess geometry, but we were able to make the idea work in infinite **three-dimensional** chess. In the last section of the article, we prove:

Theorem. Every countable ordinal arises as the game value of an infinite position of infinite three-dimensional chess. Thus, the omega one of infinite three dimensional chess is as large as it could possibly be, true $\omega_1$.

Here is a part of the position. Imagine the layers stacked atop each other, with $\alpha$ at the bottom and further layers below and above. The black king had entered at $\alpha$e4, was checked from below and has just moved to $\beta$e5. Pushing a pawn with check, white continues with 1.$\alpha$e4+ K$\gamma$e6 2.$\beta$e5+ K$\delta$e7 3.$\gamma$e6+ K$\epsilon$e8 4.$\delta$e7+, forcing black to climb the stairs (the pawn advance 1.$\alpha$e4+ was protected by a corresponding pawn below, since black had just been checked at $\alpha$e4).

The overall argument works in higher dimensional chess, as well as three-dimensional chess that has only finite extent in the third dimension $\mathbb{Z}\times\mathbb{Z}\times k$, for $k$ above 25 or so.

On the axiom of constructibility and Maddy’s conception of restrictive theories, Logic Workshop, February 2013

This is a talk for the CUNY Logic Workshop on February 15, 2013.

This talk will be based on my paper, A multiverse perspective on the axiom of constructibility.

Set-theorists often argue against the axiom of constructibility $V=L$ on the grounds that it is restrictive, that we have no reason to suppose that every set should be constructible and that it places an artificial limitation on set-theoretic possibility to suppose that every set is constructible. Penelope Maddy, in her work on naturalism in mathematics, sought to explain this perspective by means of the MAXIMIZE principle, and further to give substance to the concept of what it means for a theory to be restrictive, as a purely formal property of the theory.

In this talk, I shall criticize Maddy’s specific proposal. For example, it turns out that the fairly-interpreted-in relation on theories is not transitive, and similarly the maximizes-over and strongly-maximizes-over relations are not transitive. Further, the theory ZFC + `there is a proper class of inaccessible cardinals’ is formally restrictive on Maddy’s proposal, although this is not what she had desired.

Ultimately, I argue that the $V\neq L$ via maximize position loses its force on a multiverse conception of set theory, in light of the classical facts that models of set theory can generally be extended to (taller) models of $V=L$. In particular, every countable model of set theory is a transitive set inside a model of $V=L$. I shall conclude the talk by explaining various senses in which $V=L$ remains compatible with strength in set theory.

Math for six-year-olds

Today I went into my daughter’s first-grade classroom, full of six-year-old girls, and gave a presentation about Möbius bands.

We cut strips of paper and at first curled them into simple bands, cylinders, which we proved had two sides by coloring them one color on the outside and another color on the inside. Next, we cut strips and curled them around, but added a twist, to make a true Möbius band.

We cut strips of paper and at first curled them into simple bands, cylinders, which we proved had two sides by coloring them one color on the outside and another color on the inside. Next, we cut strips and curled them around, but added a twist, to make a true Möbius band.

These, of course, have only one side, a fact that the children proved by coloring it one color all the way around. And we observed that a Möbius band has only one edge.

We explored what happens with two twists, or more twists, and also what happens when you cut a Möbius band down the center, all the way around.

It is very interesting to cut a Möbius band on a line that is one-third of the way in from an edge, all the way around. What happens? Make your prediction before unraveling the pieces–how many pieces will there be? Will they be all the same size? How many twists will they have?

Overall, the whole presentation was a lot of fun. The girls were extremely curious about everything, and experimented with additional twists and additional ways of cutting. It seemed to be just the right amount of mathematical thinking, cutting and coloring for a first-grade class. To be sure, without prompting the girls made various Möbius earrings, headbands and bracelets, which I had to admit were fairly cool. One girl asked, “is this really mathematics?”

It seems I may be back in the first-grade classroom this spring, and I have in mind to teach them all how to beat their parents at Nim.

Superstrong cardinals are never Laver indestructible, and neither are extendible, almost huge and rank-into-rank cardinals, CUNY, January 2013

This is a talk for the CUNY Set Theory Seminar on February 1, 2013, 10:00 am.

Abstract. Although the large cardinal indestructibility phenomenon, initiated with Laver’s seminal 1978 result that any supercompact cardinal $\kappa$ can be made indestructible by $\lt\kappa$-directed closed forcing and continued with the Gitik-Shelah treatment of strong cardinals, is by now nearly pervasive in set theory, nevertheless I shall show that no superstrong strong cardinal—and hence also no $1$-extendible cardinal, no almost huge cardinal and no rank-into-rank cardinal—can be made indestructible, even by comparatively mild forcing: all such cardinals $\kappa$ are destroyed by $\text{Add}(\kappa,1)$, by $\text{Add}(\kappa,\kappa^+)$, by $\text{Add}(\kappa^+,1)$ and by many other commonly considered forcing notions.

This is very recent joint work with Konstantinos Tsaprounis and Joan Bagaria.

The use and value of mathoverflow

François Dorais has created a discussion on the MathOverflow discussion site, How is mathoverflow useful for me? in which he is soliciting response from MO users. Here is what I wrote there:

The principal draw of mathoverflow for me is the unending supply of extremely interesting mathematics, an eternal fountain of fascinating questions and answers. The mathematics here is simply compelling.

I feel that mathoverflow has enlarged me as a mathematician. I have learned a huge amount here in the past few years, particularly concerning how my subject relates to other parts of mathematics. I’ve read some really great answers that opened up new perspectives for me. But just as importantly, I’ve learned a lot when coming up with my own answers. It often happens that someone asks a question in another part of mathematics that I can see at bottom has to do with how something I know about relates to their area, and so in order to answer, I must learn enough about this other subject in order to see the connection through. How fulfilling it is when a question that is originally opaque to me, because I hadn’t known enough about this other topic, becomes clear enough for me to have an answer. Meanwhile, mathoverflow has also helped me to solidify my knowledge of my own research area, often through the exercise of writing up a clear summary account of a familiar mathematical issue or by thinking about issues arising in a question concerning confusing or difficult aspects of a familiar tool or method.

Mathoverflow has also taught me a lot about good mathematical exposition, both by the example of other’s high quality writing and by the immediate feedback we all get on our posts. This feedback reveals what kind of mathematical explanation is valued by the general mathematical community, in a direct way that one does not usually get so well when writing a paper or giving a conference talk. This kind of knowledge has helped me to improve my mathematical writing in general.

So, thanks very much mathoverflow! I am grateful.

The differential operator $\frac{d}{dx}$ binds variables

Recently the question If $\frac{d}{dx}$ is an operator, on what does it operate? was asked on mathoverflow. It seems that some users there objected to the question, apparently interpreting it as an elementary inquiry about what kind of thing is a differential operator, and on this interpretation, I would agree that the question would not be right for mathoverflow. And so the question was closed down (and then reopened, and then closed again….sigh). (Update 12/6/12: it was opened again,and so I’ve now posted my answer over there.)

Meanwhile, I find the question to be more interesting than that, and I believe that the OP intends the question in the way I am interpreting it, namely, as a logic question, a question about the nature of mathematical reference, about the connection between our mathematical symbols and the abstract mathematical objects to which we take them to refer. And specifically, about the curious form of variable binding that expressions involving $dx$ seem to involve. So let me write here the answer that I had intended to post on mathoverflow:

————————-

To my way of thinking, this is a serious question, and I am not really satisfied by the other answers and comments, which seem to answer a different question than the one that I find interesting here.

The problem is this. We want to regard $\frac{d}{dx}$ as an operator in the abstract senses mentioned by several of the other comments and answers. In the most elementary situation, it operates on a functions of a single real variable, returning another such function, the derivative. And the same for $\frac{d}{dt}$.

The problem is that, described this way, the operators $\frac{d}{dx}$ and $\frac{d}{dt}$ seem to be the same operator, namely, the operator that takes a function to its derivative, but nevertheless we cannot seem freely to substitute these symbols for

one another in formal expressions. For example, if an instructor were to write $\frac{d}{dt}x^3=3x^2$, a student might object, “don’t you mean $\frac{d}{dx}$?” and the instructor would likely reply, “Oh, yes, excuse me, I meant $\frac{d}{dx}x^3=3x^2$. The other expression would have a different meaning.”

But if they are the same operator, why don’t the two expressions have the same meaning? Why can’t we freely substitute different names for this operator and get the same result? What is going on with the logic of reference here?

The situation is that the operator $\frac{d}{dx}$ seems to make sense only when applied to functions whose independent variable is described by the symbol “x”. But this collides with the idea that what the function is at bottom has nothing to do with the way we represent it, with the particular symbols that we might use to express which function is meant. That is, the function is the abstract object (whether interpreted in set theory or category theory or whatever foundational theory), and is not connected in any intimate way with the symbol “$x$”. Surely the functions $x\mapsto x^3$ and $t\mapsto t^3$, with the same domain and codomain, are simply different ways of describing exactly the same function. So why can’t we seem to substitute them for one another in the formal expressions?

The answer is that the syntactic use of $\frac{d}{dx}$ in a formal expression involves a kind of binding of the variable $x$.

Consider the issue of collision of bound variables in first order logic: if $\varphi(x)$ is the assertion that $x$ is not maximal with respect to $\lt$, expressed by $\exists y\ x\lt y$, then $\varphi(y)$, the assertion that $y$ is not maximal, is not correctly described as the assertion $\exists y\ y\lt y$, which is what would be obtained by simply replacing the occurrence of $x$ in $\varphi(x)$ with the symbol $y$. For the intended meaning, we cannot simply syntactically replace the occurrence of $x$ with the symbol $y$, if that occurrence of $x$ falls under the scope of a quantifier.

Similarly, although the functions $x\mapsto x^3$ and $t\mapsto t^3$ are equal as functions of a real variable, we cannot simply syntactically substitute the expression $x^3$ for $t^3$ in $\frac{d}{dt}t^3$ to get $\frac{d}{dt}x^3$. One might even take the latter as a kind of ill-formed expression, without further explanation of how $x^3$ is to be taken as a function of $t$.

So the expression $\frac{d}{dx}$ causes a binding of the variable $x$, much like a quantifier might, and this prevents free substitution in just the way that collision does. But the case here is not quite the same as the way $x$ is a bound variable in $\int_0^1 x^3\ dx$, since $x$ remains free in $\frac{d}{dx}x^3$, but we would say that $\int_0^1 x^3\ dx$ has the same meaning as $\int_0^1 y^3\ dy$.

Of course, the issue evaporates if one uses a notation, such as the $\lambda$-calculus, which insists that one be completely explicit about which syntactic variables are to be regarded as the independent variables of a functional term, as in $\lambda x.x^3$, which means the function of the variable $x$ with value $x^3$. And this is how I take several of the other answers to the question, namely, that the use of the operator $\frac{d}{dx}$ indicates that one has previously indicated which of the arguments of the given function is to be regarded as $x$, and it is with respect to this argument that one is differentiating. In practice, this is almost always clear without much remark. For example, our use of $\frac{\partial}{\partial x}$ and $\frac{\partial}{\partial y}$ seems to manage very well in complex situations, sometimes with dozens of variables running around, without adopting the onerous formalism of the $\lambda$-calculus, even if that formalism is what these solutions are essentially really about.

Meanwhile, it is easy to make examples where one must be very specific about which variables are the independent variable and which are not, as Todd mentions in his comment to David’s answer. For example, cases like

$$\frac{d}{dx}\int_0^x(t^2+x^3)dt\qquad

\frac{d}{dt}\int_t^x(t^2+x^3)dt$$

are surely clarified for students by a discussion of the usage of variables in formal expressions and more specifically the issue of bound and free variables.