I’d like to continue a bit further my exploration of some principles of determinacy for proper-class games; it turns out that these principles have a surprising set-theoretic strength. A few weeks ago, I explained that the determinacy of proper-class open games and even clopen games implies Con(ZFC) and much more. Today, I’d like to prove that clopen determinacy is exactly equivalent over GBC to the principle of transfinite recursion along proper-class well-founded relations. Thus, GBC plus either of these principles is a strictly intermediate set theory between GBC and KM.

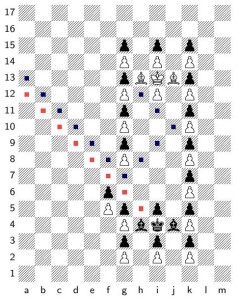

The principle of clopen determinacy for class games is the assertion that in any two-player infinite game of perfect information whose winning condition is a clopen class, there is a winning strategy for one of the players. Players alternately play moves in a playing space $X$, thereby creating a particular play $\vec a\in X^\omega$, and the winner is determined according to whether $\vec a$ is in a certain fixed payoff class $U\subset X^\omega$ or not. One has an open game when this winning condition class $U$ is open in the product topology (using the discrete topology on $X$). A game is open for a player if and only if every winning play for that player has an initial segment, all of whose extensions are also winning for that player. So the game is won for an open player at a finite stage of play. A clopen game, in contrast, has a payoff set that is open for both players. Clopen games can be equivalently cast in terms of the game tree, consisting of positions in the game where the winner is not yet determined, and where play terminates when the winner is known. Namely, a game is clopen exactly when this game tree is well-founded, so that in every play, the outcome is known already at a finite stage.

A strategy is a class function $\sigma:X^{<\omega}\to X$ that instructs the player what to play next, given a position of partial play, and the strategy is winning for a player if all plays that accord with it satisfy the winning condition for that player.

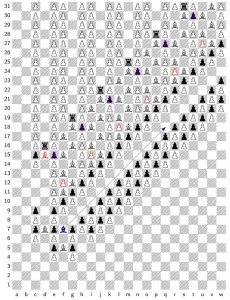

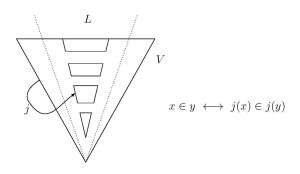

The principle of transfinite recursion along well-founded class relations is the assertion that we may undertake recursive definitions along any class well-founded partial order relation. That is, suppose that $\lhd$ is a class well-founded partial order relation on a class $A$, and suppose that $\varphi(F,a,y)$ is a formula, using only first-order quantifiers but having a class variable $F$, which is functional in the sense that for any class $F$ and any set $a\in A$ there is a unique $y$ such that $\varphi(F,a,y)$. The idea is that $\varphi(F,a,y)$ expresses the recursive rule to be iterated, and a solution of the recursion is a class function $F$ such that $\varphi(F\upharpoonright a,a,F(a))$ holds for every $a\in A$, where $F\upharpoonright a$ means the restriction of $F$ to the class $\{ b\in A\mid b\lhd a\}$. Thus, the value $F(a)$ is determined by the class of previous values $F(b)$ for $b\lhd a$. The principle of transfinite recursion along class well-founded relations is the assertion scheme that for every such well-founded partial order class $\langle A,\lhd\rangle$ and any recursive rule $\varphi$ as above, there is a solution.

In the case that the relation $\lhd$ is set-like, which means that the predecessors $\{b\mid b\lhd a\}$ of any point $a$ form a set (rather than a proper class), then GBC easily proves that there is a unique solution class, which furthermore is definable from $\lhd$. Namely, one can show that every $a\in A$ has a partial solution that obeys the recursive rule at least up to $a$, and furthermore all such partial solutions agree below $a$, because there can be no $\lhd$-minimal violation of this. It follows that the class function $F$ unifying these partial solutions is a total solution to the recursion. Similarly, GBC can prove that there are solutions to other transfinite recursion instances where the well-founded relation is not necessarily set-like, such as a recursion of length $\text{Ord}+\text{Ord}$ or even much longer.

Meanwhile, if GBC is consistent, then it cannot in general prove that transfinite recursions along non-set-like well-founded relations always succeed, since this principle would imply that there is a truth-predicate for first-order truth, as the Tarskian conditions are precisely such a recursion on a well-founded relation based on the complexity of formulas. (That relation is not set-like, since when considering the truth of $\exists x\,\psi(x,\vec a)$, we want to consider the truth of $\psi(b,\vec a)$ for any parameter $b$, and there are a proper class of such $b$.) Thus, GBC plus transfinite recursion (or plus clopen determinacy) is strictly stronger than GBC, although it is provable in Kelley-Morse set theory KM essentially the same as GBC proves the set-like special case.

Theorem. Assume GBC. Then the following are equivalent.

- Clopen determinacy for class games. That is, for any two-player game of perfect information whose payoff class is both open and closed, there is a winning strategy for one of the players.

- Transfinite recursion for proper class well-founded relations (not necessarily set-like).

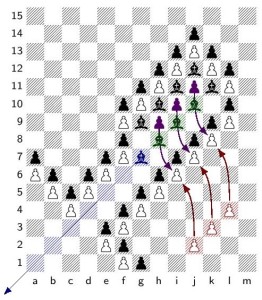

Proof. ($2\to 1$) Assume the principle of transfinite recursion for proper class well-founded relations, and suppose we are faced with a clopen game. Consider the game tree $T$, consisting of positions arising during play, up to the moment that a winner is known. This tree is well-founded because the game is clopen. Let us label the terminal nodes of the tree with I or II according to who has won the game in that position, and more generally, let us label all the nodes of the tree with I or II according to the following transfinite recursion: if a node has I to play, then it will have label I if there is a move to a node labeled I, and otherwise II; and similarly when it is II to play. By the principle of transfinite recursion, there is a labeling of the entire tree that accords with this recursive rule. It is now easy to see that if the initial node is labeled with I, then player I has a winning strategy, which is simply to stay on the nodes labeled I. Note that player II cannot play in one move from a node labeled I to one labeled II. Similarly, if the initial node is labeled II, then player II has a winning strategy; and so the game is determined, as desired.

($1\to 2$) Conversely, let us assume the principle of clopen determinacy for class games. Suppose we are faced with a recursion along a class relation $\lhd$ on a class $A$, using a recursion rule $\varphi(F,a,y)$. We shall define a certain clopen game, and prove that any winning strategy for this game will produce a solution for the recursion.

It will be convenient to assume that $\varphi(F,a,y)$ is strongly functional, meaning that not only does it define a function as we have mentioned in $V$, but also that $\varphi(F,a,y)$ defines a function $(F,a)\mapsto y$ when used over any model $\langle V_\theta,\in,F\rangle$ for any class $F\subset V_\theta$. The strongly functional property can be achieved simply by replacing the formula with the assertion that $\varphi(F,a,y)$, if $y$ is unique such that this holds, and otherwise $y=\emptyset$.

At first, let us consider a slightly easier game, which will be open rather than clopen; a bit later, we shall revise this game to a clopen game. The game is the recursion game, which will be very much like the truth-telling game of my previous post, Open determinacy for proper class games implies Con(ZFC) and much more. Namely, we have two players, the challenger and the truth-teller. The challenger will issues challenges about truth in a structure $\langle V,\in,\lhd,F\rangle$, where $\lhd$ is the well-founded class relation and $F$ is a class function, not yet specified. Specifically, the challenger is allowed to ask about the truth of any formula $\varphi(\vec a)$ in this structure, and to inquire as to the value of $F(a)$ for any particular $a$. The truth-teller, as before, will answer the challenges by saying either that $\varphi(\vec a)$ is true or false, and in the case $\varphi(\vec a)=\exists x\,\psi(x,\vec a)$ and the formula was declared true, by also giving a witness $b$ and declaring $\psi(b,\vec a)$ is true; and the truth-teller must specify a specific value for $F(a)$ for any particular $a$. The truth-teller loses immediately, if she should ever violate Tarski’s recursive definition of truth; and she also loses unless she declares the recursive rules $\varphi(F\upharpoonright a,a,F(a))$ to be true. Since these violations occur at a finite stage of play if they do at all, the game is open for the challenger.

Lemma. The challenger has no winning strategy in the recursion game.

Proof. Suppose that $\sigma$ is a strategy for the challenger. So $\sigma$ is a class function that instructs the challenger how to play next, given a position of partial play. By the reflection theorem, there is an ordinal $\theta$ such that $V_\theta$ is closed under $\sigma$, and using the satisfaction class that comes from clopen determinacy, we may actually also arrange that $\langle V_\theta,\in,\lhd\cap V_\theta,\sigma\cap V_\theta\rangle\prec\langle V,\in,\lhd,\sigma\rangle$. Consider the relation $\lhd\cap V_\theta$, which is a well-founded relation on $A\cap V_\theta$. The important point is that this relation is now a set, and in GBC we may certainly undertake transfinite recursions along well-founded set relations. Thus, there is a function $f:A\cap V_\theta\to V_\theta$ such that $\langle V_\theta,\in,f\rangle$ satisfies $\varphi(f\upharpoonright a,a,f(a))$ for all $a\in V_\theta$, where $f\upharpoonright a$ means restricting $f$ to the predecessors of $a$ in $V_\theta$, and this may not be all the predecessors of $a$ with respect to $\lhd$, which may not be set-like. Note that this is the place where we use our assumption that $\varphi$ was strongly functional, since we want to ensure that it can still be used to define a valid recursion over $\lhd\cap V_\theta$. (We are not claiming that $\langle V_\theta,\in,\lhd\cap V_\theta,f\rangle$ models $\text{ZFC}(\lhd,f)$.)

Consider now the play of the recursion game in $V$, where the challenger uses the strategy $\sigma$ and the truth-teller plays in accordance with $\langle V_\theta,\in,\lhd\cap V_\theta,f\rangle$. Since $V_\theta$ was closed under $\sigma$, the challenger will never issue challenges outside of $V_\theta$. And since the function $f$ fulfills the recursion $\varphi(f\upharpoonright a,a,f(a))$ in this structure, the truth-teller will not be trapped in any violation of the Tarski conditions or the recursion condition. Thus, the truth-teller will win this instance of the game, and so $\sigma$ was not a winning strategy for the challenger, as desired. QED

Lemma. The truth-teller has a winning strategy in the recursion game if and only if there is a solution of the recursion.

Proof. If there is a solution $F$ of the recursion, then by clopen determinacy, we also get a satisfaction class for the structure $\langle V,\in,\lhd,F\rangle$, and the truth-teller can answer all queries of the challenger by referring to what is actually true in this structure. This will be winning for the truth-teller, since the actual truth obeys the Tarskian conditions and the recursive rule.

Conversely, suppose that $\tau$ is a winning strategy for the truth-teller in the recursion game. We claim that the truth assertions made by $\tau$ do not depend on the order in which challenges are made by the challenger; they all cohere with one another. This is easy to see for formulas not involving $F$ by induction on formulas, for if the truth of a formula $\psi(\vec a)$ is independent of play, then also the truth of $\neg\psi(\vec a)$ is as well, and similarly if $\exists x\psi(x,\vec a)$ is declared true with witness $\psi(b,\vec a)$, then by induction $\psi(b,\vec a)$ is independent of the play, in which case $\exists x\psi(x,\vec a)$ must always be declared true by $\tau$ independently of the order of play by the challenger (although the particular witness $b$ provided by $\tau$ may depend on the play). Now, let us also argue that the values of $F(a)$ declared by $\tau$ are also independent of the order of play. If not, there is some $\lhd$-least $a$ where this fails. (Note that such an $a$ exists, since $\tau$ is a class, and we can define from $\tau$ the class of $a$ for which the value of $F(a)$ declared by $\tau$ depends on the order of play; without $\tau$, one might have expected to need $\Pi^1_1$-comprehension to find a minimal $a$ where the recursion fails.) As in the truth-telling game, the truth assertions made by $\tau$ about $\langle V,\in,\lhd,F\upharpoonright a\rangle$, where $F\upharpoonright a$ is the class function of values that are determined by $\tau$ on $b\lhd a$, must not depend on the order of play. Since the recursion rule $\varphi(F\upharpoonright a,a,y)$ is functional, there is only one value $y=F(a)$ for which this formula can be truthfully held, and so if some play causes $\tau$ to play a different value for $F(a)$, the challenger can in finitely many additional moves (bounded by the syntactic complexity of $\varphi$) trap the truth-teller in a violation of the Tarskian conditions or the recursion condition. Thus, the values of $F(a)$ declared by $\tau$ must in fact all cohere independently of the order of play, and so $\tau$ is describing a class function $F:A\to V$ such that $\varphi(F\upharpoonright a,a,F(a))$ is true for every $a\in A$. So the recursion has a solution, as desired. QED

So far, we have established that the principle of open determinacy implies the principle of transfinite recursion along well-founded class relations. In order to improve this implication to use only clopen determinacy rather than open determinacy, we modify the game to become a clopen game rather than an open game.

Consider the clopen form of the recursion game, where we insist also that the challenger announce on the first move a natural number $n$, such that the challenger loses if the truth-teller survives for at least $n$ moves. This is now a clopen game, since the winner will be known by that time, either because the truth-teller will violate the Tarski conditions or the recursion condition, or else the challenger’s limit on play will expire.

Since the modified version of the game is even harder for the challenger, there can still be no winning strategy for the challenger. So by the principle of clopen determinacy, there is a winning strategy $\tau$ for the truth-teller. This strategy is allowed to make decisions based on the number $n$ announced by the challenger on the first move, and it will no longer necessarily be the case that the theory declared true by $\tau$ will be independent of the order of play. Nevertheless, it will be the case, we claim, that the theory declared true by $\tau$ for all plays with sufficiently large $n$ (and with sufficiently many remaining moves) will be independent of the order of play. One can see this by observing that if an assertion $\psi(\vec a)$ is independent in this sense, then also $\neg\psi(\vec a)$ will be independent in this sense, for otherwise there would be plays with large $n$ giving different answers for $\neg\psi(\vec a)$ and we could then challenge with $\psi(\vec a)$, which would have to give different answers or else $\tau$ would not win. Similarly, since $\tau$ is winning, one can see that allowing the challenger to specify a bound on the total length of play does not prevent the arguments above showing that $\tau$ describes a coherent solution function $F:A\to V$ satisfying the recursion $\varphi(F\upharpoonright a,a,F(a))$, provided that one looks only at plays in which there are sufficiently many moves remaining. There cannot be a $\lhd$-least $a$ where the value of $F(a)$ is not determined in this sense, and so on as before.

Thus, we have proved that the principle of clopen determinacy for class games is equivalent to the principle of transfinite recursion along well-founded class relations. QED

The material in this post will become part of a joint project with Victoria Gitman and Thomas Johnstone. We are currently investigating several further related issues.

.jpg)

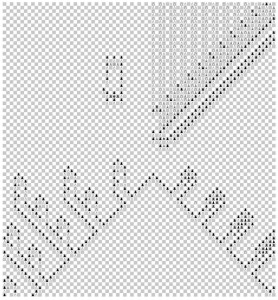

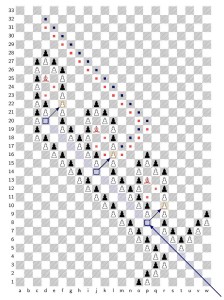

I was recently asked an interesting elementary question about the number of possible order types of the final segments of an ordinal, and in particular, whether there could be an ordinal realizing infinitely many different such order types as final segments. Since I found it interesting, let me write here how I replied.

I was recently asked an interesting elementary question about the number of possible order types of the final segments of an ordinal, and in particular, whether there could be an ordinal realizing infinitely many different such order types as final segments. Since I found it interesting, let me write here how I replied.