Have you ever observed carefully how a slinky falls? Suspend a slinky from one end, letting it hang freely in the air under its own weight, and then, let go! The slinky begins to fall. The top of the slinky, of course, begins to fall the moment you let go of it. But what happens at the bottom of the slinky? Does it also start to fall at the same moment you release the top? Or perhaps it moves upward, as the slinky contracts as it falls? Or does the bottom of the slinky simply hang motionless in the air for a time?

The surprising fact is that indeed the bottom of the slinky doesn’t move at all when you release the top of the slinky! It hangs momentarily motionless in the air in exactly the same coiled configuration that it had before the drop. This is the surprising slinky drop effect.

My son (age 13, eighth grade) took up the topic for his science project this year at school. He wanted to establish the basic phenomenon of the slinky drop effect and to investigate some of the subtler aspects of it. For a variety of different slinky types, he filmed the slinky drops against a graded background with high-speed camera, and then replayed them in slow motion to watch carefully and take down the data. Here are a few sample videos. He made about a dozen drops altogether. For the actual data collection, the close-up videos were more useful. Note the ring markers A, B, C, and so on, in some of the videos.

See more videos here.

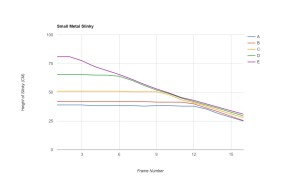

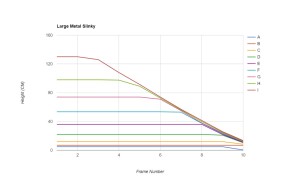

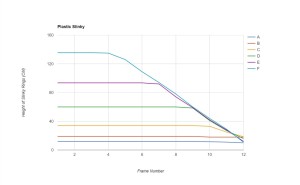

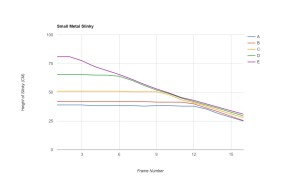

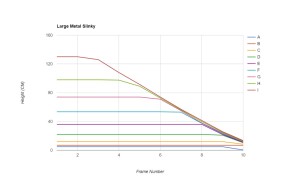

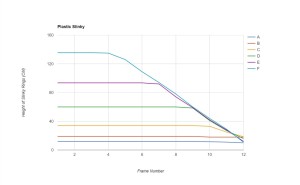

For each slinky drop video, he went through the frames and recorded the vertical location of various marked rings (you can see the labels A, B, C and so on in some of the videos above) into a spreadsheet. From this data he then produced graphs such as the following for each slinky drop:

In each case, you can see clearly in the graph the moment when the top of the slinky is released, since this is the point at which the top line begins to descend. The thing to notice next — the main slinky drop effect — is that the lower parts of the slinky do not move at the same time. Rather, the lower lines remain horizontal for some time after the drop point. Basically, they remain horizontal until the bulk of the slinky nearly descends upon them. So the experiments clearly establish the main slinky drop phenomenon: the bottom of the slinky remains motionless for a time hanging in the air unchanged after the top is released.

In addition to this effect, however, my son was focused on investigating a much more subtle aspect of the slinky drop phenomenon. Namely, when exactly does the bottom of the slinky start to move? Some have said that the bottom moves only when the top catches up to it; but my son hypothesized, based on observations, as well as discussions with his father and uncles, that the bottom should start to move slightly before the bulk of the slinky meets it. Namely, he thought that when you release the top of the slinky, a wave of motion travels through the slinky, and this wave travels slightly fast than the top of the slinky falls. The bottom moves, he hypothesized, when the wave front first gets to the bottom.

His data contains some confirming evidence for this subtler hypothesis, but for some of the drops, the experiment was inconclusive on this smaller effect. Overall, he had a great time undertaking the science project.

June 2016 Update: On the basis of his science fair poster and presentation, my son was selected as nominee to the Broadcom Masters national science fair competition! He is now competing against other nominees (top 10% of participating science fairs) for a chance to present his research in Washington at the final national competition next October.

September 2016 Update: My son has now been selected as a Broadcom Masters semi-finalist, placing him in the top 300 amongst more than 6000 nominees. The finalists will be chosen in a few weeks, with the chance to present in Washington, D.C.

Slinky drop on YouTube | Modeling a falling slinky (Wired)

Explaining an astonishing slinky | Slinky drop on physics.stackexchange

Cross & Wheatland, “Modeling a falling slinky”