The toy multiverse of all countable models of set theory is upward closed under countably many successive forcing extensions of bounded size…

The toy multiverse of all countable models of set theory is upward closed under countably many successive forcing extensions of bounded size…

I’d like to explain a topic from my recent paper

G. Fuchs, J. D. Hamkins, J. Reitz, Set-theoretic geology, to appear in the Annals of Pure and Applied Logic.

We just recently made the final revisions, and the paper is available if you follow the title link through to the arxiv. Most of the geology article proceeds from a downward-oriented focus on forcing, looking from a universe $V$ down to its grounds, the inner models $W$ over which $V$ might have arisen by forcing $V=W[G]$. Thus, the set-theoretic geology project arrives at deeper and deeper grounds and the mantle and inner mantle concepts.

One section of the paper, however, has an upward-oriented focus, namely, $\S2$ A brief upward glance, and it is that material about which I’d like to write here, because I find it to be both interesting and comparatively accessible, but also because the topic proceeds from a different perspective than the rest of the geology paper, and so I am a little fearful that it may get lost there.

First is the observation that I first heard from W. Hugh Woodin in the early 1990s.

$\newcommand\P{\mathbb{P}}\newcommand\Q{\mathbb{Q}}\newcommand\R{\mathbb{R}}\newcommand\of{\subset}\newcommand\cross{\times}$

Observation. If $W$ is a countable model of ZFC set theory, then there are forcing extensions $W[c]$ and $W[d]$, both obtained by adding a Cohen real, which are non-amalgamable in the sense that there can be no model of ZFC with the same ordinals as $W$ containing both $W[c]$ and $W[d]$. Thus, the family of forcing extensions of $W$ is not upward directed.

Proof. Since $W$ is countable, let $z$ be a real coding the entirety of $W$. Enumerate the dense subsets $\langle D_n\mid n<\omega\rangle$ of the Cohen forcing $\text{Add}(\omega,1)$ in $W$. We construct $c$ and $d$ in stages. We begin by letting $c_0$ be any element of $D_0$. Let $d_0$ consist of exactly as many $0$s as $|c_0|$, followed by a $1$, followed by $z(0)$, and then extended to an element of $D_0$. Continuing, $c_{n+1}$ extends $c_n$ by adding $0$s until the length of $d_n$, and then a $1$, and then extending into $D_{n+1}$; and $d_{n+1}$ extends $d_n$ by adding $0$s to the length of $c_{n+1}$, then a $1$, then $z(n)$, then extending into $D_{n+1}$. Let $c=\bigcup c_n$ and $d=\bigcup d_n$. Since we met all the dense sets in $W$, we know that $c$ and $d$ are $W$-generic Cohen reals, and so we may form the forcing extensions $W[c]$ and $W[d]$. But if $W\subset U\models\text{ZFC}$ and both $c$ and $d$ are in $U$, then in $U$ we may reconstruct the map $n\mapsto\langle c_n,d_n\rangle$, by giving attention to the blocks of $0$s in $c$ and $d$. From this map, we may reconstruct $z$ in $U$, which reveals all the ordinals of $W$ to be countable, a contradiction if $U$ and $W$ have the same ordinals. QED

Most of the results here concern forcing extensions of an arbitrary countable model of set theory, which of course includes the case of ill-founded models. Although there is no problem with forcing extensions of ill-founded models, when properly carried out, the reader may prefer to focus on the case of countable transitive models for the results in this section, and such a perspective will lose very little of the point of our observations.

The method of the observation above is easily generalized to produce three $W$-generic Cohen reals $c_0$, $c_1$ and $c_2$, such that any two of them can be amalgamated, but the three of them cannot. More generally:

Observation. If $W$ is a countable model of ZFC set theory, then for any finite $n$ there are $W$-generic Cohen reals $c_0,c_1,\ldots,c_{n-1}$, such that any proper subset of them are mutually $W$-generic, so that one may form the generic extension $W[\vec c]$, provided that $\vec c$ omits at least one $c_i$, but there is no forcing extension $W[G]$ simultaneously extending all $W[c_i]$ for $i<n$. In particular, the sequence $\langle c_0,c_1,\ldots,c_{n-1}\rangle$ cannot be added by forcing over $W$.

Let us turn now to infinite linearly ordered sequences of forcing extensions. We show first in the next theorem and subsequent observation that one mustn’t ask for too much; but nevertheless, after that we shall prove the surprising positive result, that any increasing sequence of forcing extensions over a countable model $W$, with forcing of uniformly bounded size, is bounded above by a single forcing extension $W[G]$.

Theorem. If $W$ is a countable model of ZFC, then there is an increasing sequence of set-forcing extensions of $W$ having no upper bound in the generic multiverse of $W$. $$W[G_0]\of W[G_1]\of\cdots\of W[G_n]\of\cdots$$

Proof. Since $W$ is countable, there is an increasing sequence $\langle\gamma_n\mid n<\omega\rangle$ of ordinals that is cofinal in the ordinals of $W$. Let $G_n$ be $W$-generic for the collapse forcing $\text{Coll}(\omega,\gamma_n)$, as defined in $W$. (By absorbing the smaller forcing, we may arrange that $W[G_n]$ contains $G_m$ for $m<n$.) Since every ordinal of $W$ is eventually collapsed, there can be no set-forcing extension of $W$, and indeed, no model with the same ordinals as $W$, that contains every $W[G_n]$. QED

But that was cheating, of course, since the sequence of forcing notions is not even definable in $W$, as the class $\{\gamma_n\mid n<\omega\}$ is not a class of $W$. A more intriguing question would be whether this phenomenon can occur with forcing notions that constitute a set in $W$, or (equivalently, actually) whether it can occur using always the same poset in $W$. For example, if $W[c_0]\of W[c_0][c_1]\of W[c_0][c_1][c_2]\of\cdots$ is an increasing sequence of generic extensions of $W$ by adding Cohen reals, then does it follow that there is a set-forcing extension $W[G]$ of $W$ with $W[c_0]\cdots[c_n]\of W[G]$ for every $n$? For this, we begin by showing that one mustn’t ask for too much:

Observation. If $W$ is a countable model of ZFC, then there is a sequence of forcing extensions $W\of W[c_0]\of W[c_0][c_1]\of W[c_0][c_1][c_2]\of\cdots$, adding a Cohen real at each step, such that there is no forcing extension of $W$ containing the sequence $\langle c_n\mid n<\omega\rangle$.

Proof. Let $\langle d_n\mid n<\omega\rangle$ be any $W$-generic sequence for the forcing to add $\omega$ many Cohen reals over $W$. Let $z$ be any real coding the ordinals of $W$. Let us view these reals as infinite binary sequences. Define the real $c_n$ to agree with $d_n$ on all digits except the initial digit, and set $c_n(0)=z(n)$. That is, we make a single-bit change to each $d_n$, so as to code one additional bit of $z$. Since we have made only finitely many changes to each $d_n$, it follows that $c_n$ is an $W$-generic Cohen real, and also $W[c_0]\cdots[c_n]=W[d_0]\cdots [d_n]$. Thus, we have $$W\of W[c_0]\of W[c_0][c_1]\of W[c_0][c_1][c_2]\of\cdots,$$ adding a generic Cohen real at each step. But there can be no forcing extension of $W$ containing $\langle c_n\mid n<\omega\rangle$, since any such extension would have the real $z$, revealing all the ordinals of $W$ to be countable. QED

We can modify the construction to allow $z$ to be $W$-generic, but collapsing some cardinals of $W$. For example, for any cardinal $\delta$ of $W$, we could let $z$ be $W$-generic for the collapse of $\delta$. Then, if we construct the sequence $\langle c_n\mid n<\omega\rangle$ as above, but inside $W[z]$, we get a sequence of Cohen real extensions $$W\of W[c_0]\of W[c_0][c_1]\of W[c_0][c_1][c_2]\of\cdots$$ such that $W[\langle c_n\mid n<\omega\rangle]=W[z]$, which collapses $\delta$.

But of course, the question of whether the models $W[c_0][c_1]\cdots[c_n]$ have an upper bound is not the same question as whether one can add the sequence $\langle c_n\mid n<\omega\rangle$, since an upper bound may not have this sequence. And in fact, this is exactly what occurs, and we have a surprising positive result:

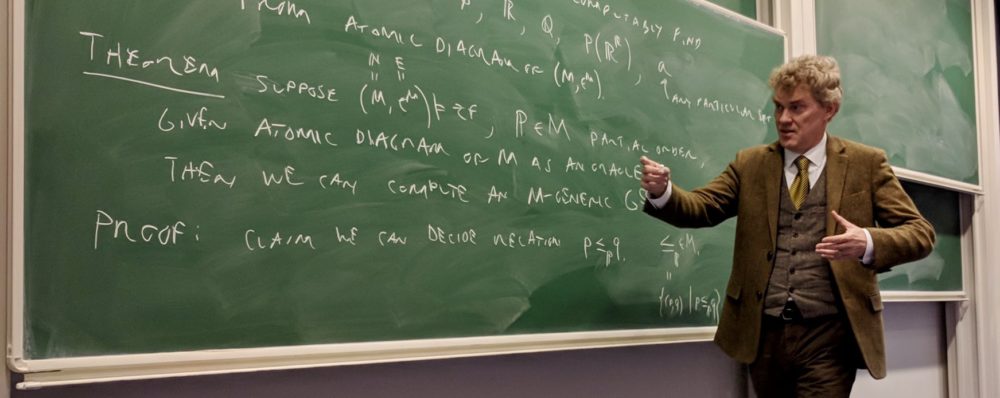

Theorem. Suppose that $W$ is a countable model of \ZFC, and $$W[G_0]\of W[G_1]\of\cdots\of W[G_n]\of\cdots$$ is an increasing sequence of forcing extensions of $W$, with $G_n\of\Q_n\in W$ being $W$-generic. If the cardinalities of the $\Q_n$’s in $W$ are bounded in $W$, then there is a set-forcing extension $W[G]$ with $W[G_n]\of W[G]$ for all $n<\omega$.

Proof. Let us first make the argument in the special case that we have $$W\of W[g_0]\of W[g_0][g_1]\of\cdots\of W[g_0][g_1]\cdots[g_n]\of\cdots,$$ where each $g_n$ is generic over the prior model for forcing $\Q_n\in W$. That is, each extension $W[g_0][g_1]\cdots[g_n]$ is obtained by product forcing $\Q_0\cross\cdots\cross\Q_n$ over $W$, and the $g_n$ are mutually $W$-generic. Let $\delta$ be a regular cardinal with each $\Q_n$ having size at most $\delta$, built with underlying set a subset of $\delta$. In $W$, let $\theta=2^\delta$, let $\langle \R_\alpha\mid\alpha<\theta\rangle$ enumerate all posets of size at most $\delta$, with unbounded repetition, and let $\P=\prod_{\alpha<\theta}\R_\alpha$ be the finite-support product of these posets. Since each factor is $\delta^+$-c.c., it follows that the product is $\delta^+$-c.c. Since $W$ is countable, we may build a filter $H\of\P$ that is $W$-generic. In fact, we may find such a filter $H\of\P$ that meets every dense set in $\bigcup_{n<\omega}W[g_0][g_1]\cdots[g_n]$, since this union is also countable. In particular, $H$ and $g_0\cross\cdots\cross g_n$ are mutually $W$-generic for every $n<\omega$. The filter $H$ is determined by the filters $H_\alpha\of\R_\alpha$ that it adds at each coordinate.

Next comes the key step. Externally to $W$, we may find an increasing sequence $\langle \theta_n\mid n<\omega\rangle$ of ordinals cofinal in $\theta$, such that $\R_{\theta_n}=\Q_n$. This is possible because the posets are repeated unboundedly, and $\theta$ is countable in $V$. Let us modify the filter $H$ by surgery to produce a new filter $H^*$, by changing $H$ at the coordinates $\theta_n$ to use $g_n$ rather than $H_{\theta_n}$. That is, let $H^*_{\theta_n}=g_n$ and otherwise $H^*_\alpha=H_\alpha$, for $\alpha\notin\{\theta_n\mid n<\omega\}$. It is clear that $H^*$ is still a filter on $\P$. We claim that $H^*$ is $W$-generic. To see this, suppose that $A\of\P$ is any maximal antichain in $W$. By the $\delta^+$-chain condition and the fact that $\text{cof}(\theta)^W>\delta$, it follows that the conditions in $A$ have support bounded by some $\gamma<\theta$. Since the $\theta_n$ are increasing and cofinal in $\theta$, only finitely many of them lay below $\gamma$, and we may suppose that there is some largest $\theta_m$ below $\gamma$. Let $H^{**}$ be the filter derived from $H$ by performing the surgical modifications only on the coordinates $\theta_0,\ldots,\theta_m$. Thus, $H^*$ and $H^{**}$ agree on all coordinates below $\gamma$. By construction, we had ensured that $H$ and $g_0\cross\cdots\cross g_m$ are mutually generic over $W$ for the forcing $\P\cross\Q_0\cross\cdots\cross\Q_m$. This poset has an automorphism swapping the latter copies of $\Q_i$ with their copy at $\theta_i$ in $\P$, and this automorphism takes the $W$-generic filter $H\cross g_0\cross\cdots\cross g_m$ exactly to $H^{**}\cross H_{\theta_0}\cross\cdots \cross H_{\theta_m}$. In particular, $H^{**}$ is $W$-generic for $\P$, and so $H^{**}$ meets the maximal antichain $A$. Since $H^*$ and $H^{**}$ agree at coordinates below $\gamma$, it follows that $H^*$ also meets $A$. In summary, we have proved that $H^*$ is $W$-generic for $\P$, and so $W[H^*]$ is a set-forcing extension of $W$. By design, each $g_n$ appears at coordinate $\theta_n$ in $H^*$, and so $W[g_0]\cdots[g_n]\of W[H^*]$ for every $n<\omega$, as desired.

Finally, we reduce the general case to this special case. Suppose that $W[G_0]\of W[G_1]\of\cdots\of W[G_n]\of\cdots$ is an increasing sequence of forcing extensions of $W$, with $G_n\of\Q_n\in W$ being $W$-generic and each $\Q_n$ of size at most $\kappa$ in $W$. By the standard facts surrounding finite iterated forcing, we may view each model as a forcing extension of the previous model $$W[G_{n+1}]=W[G_n][H_n],$$ where $H_n$ is $W[G_n]$-generic for the corresponding quotient forcing $\Q_n/G_n$ in $W[G_n]$. Let $g\of\text{Coll}(\omega,\kappa)$ be $\bigcup_n W[G_n]$-generic for the collapse of $\kappa$, so that it is mutually generic with every $G_n$. Thus, we have the increasing sequence of extensions $W[g][G_0]\of W[g][G_1]\of\cdots$, where we have added $g$ to each model. Since each $\Q_n$ is countable in $W[g]$, it is forcing equivalent there to the forcing to add a Cohen real. Furthermore, the quotient forcing $\Q_n/G_n$ is also forcing equivalent in $W[g][G_n]$ to adding a Cohen real. Thus, $W[g][G_{n+1}]=W[g][G_n][H_n]=W[g][G_n][h_n]$, for some $W[g][G_n]$-generic Cohen real $h_n$. Unwrapping this recursion, we have $W[g][G_{n+1}]=W[g][G_0][h_1]\cdots[h_n]$, and consequently $$W[g]\of W[g][G_0]\of W[g][G_0][h_1]\of W[g][G_0][h_1][h_2]\of\cdots,$$ which places us into the first case of the proof, since this is now product forcing rather than iterated forcing. QED

Definition. A collection $\{W[G_n]\mid n<\omega\}$ of forcing extensions of $W$ is finitely amalgamable over $W$ if for every $n<\omega$ there is a forcing extension $W[H]$ with $W[G_m]\of W[H]$ for all $m\leq n$. It is amalgamable over $W$ if there is $W[H]$ such that $W[G_n]\of W[H]$ for all $n<\omega$.

The next corollary shows that we cannot improve the non-amalgamability result of the initial observation to the case of infinitely many Cohen reals, with all finite subsets amalgamable.

Corollary. If $W$ is a countable model of ZFC and $\{W[G_n]\mid n<\omega\}$ is a finitely amalgamable collection of forcing extensions of $W$, using forcing of bounded size in $W$, then this collection is fully amalgamable. That is, there is a forcing extension $W[H]$ with $W[G_n]\of W[H]$ for all $n<\omega$.

Proof. Since the collection is finitely amalgamable, for each $n<\omega$ there is some $W$-generic $K$ such that $W[G_m]\of W[K]$ for all $m\leq n$. Thus, we may form the minimal model $W[G_0][G_1]\cdots[G_n]$ between $W$ and $W[K]$, and thus $W[G_0][G_1]\cdots [G_n]$ is a forcing extension of $W$. We are thus in the situation of the theorem, with an increasing chain of forcing extensions. $$W\of W[G_0]\of W[G_0][G_1]\of\cdots\of W[G_0][G_1]\cdots[G_n]\of\cdots$$ Therefore, by the theorem, there is a model $W[H]$ containing all these extensions, and in particular, $W[G_n]\of W[H]$, as desired. QED

Please go to the paper for more details and discussion.

.jpg)

The toy multiverse of all countable models of set theory is upward closed under countably many successive forcing extensions of bounded size…

The toy multiverse of all countable models of set theory is upward closed under countably many successive forcing extensions of bounded size…