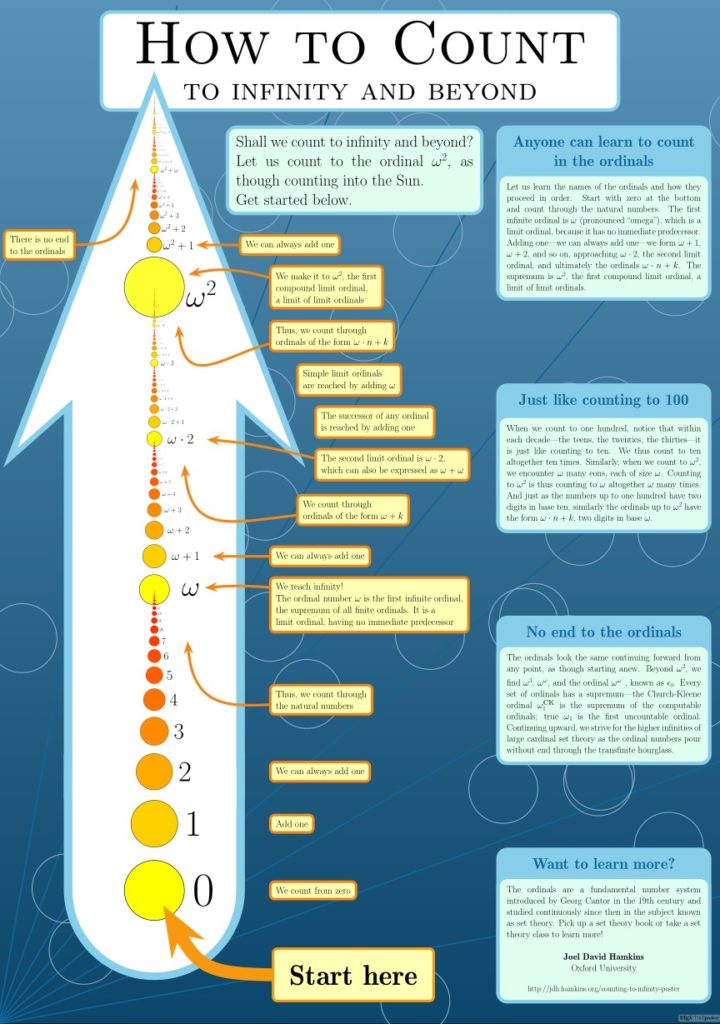

Did you know that you can add and multiply orders? For any two order structures $A$ and $B$, we can form the ordered sum $A+B$ and ordered product $A\otimes B$, and other natural operations, such as the disjoint sum $A\sqcup B$, which make altogether an arithmetic of orders. We combine orders with these operations to make new orders, often with interesting properties. Let us explore the resulting algebra of orders!

$\newcommand\Z{\mathbb{Z}}\newcommand\N{\mathbb{N}}\newcommand\Q{\mathbb{Q}}\newcommand\P{\mathbb{P}}\newcommand\iso{\cong}\newcommand\of{\subseteq}$

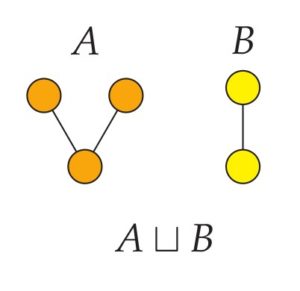

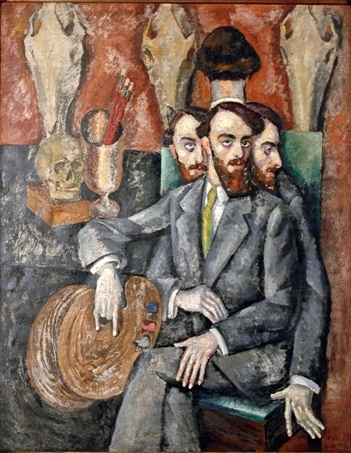

One of the most basic operations that we can use to combine two orders is the disjoint sum operation $A\sqcup B$. This is the order resulting from placing a copy of $A$ adjacent to a copy of $B$, side-by-side, forming a combined order with no instances of the order relation between the two parts. If $A$ is the orange $\vee$-shaped order here and $B$ is the yellow linear order, for example, then $A\sqcup B$ is the combined order with all five nodes.

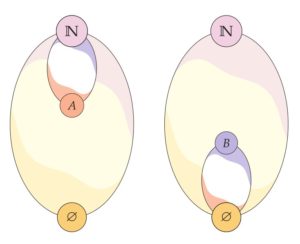

Another kind of addition is the ordered sum of two orders $A+B$, which is obtained by placing a copy of $B$ above a copy of $A$, as indicated here by adding the orange copy of $A$ and the yellow copy of $B$. Also shown is the sum $B+A$, with the summands reversed, so that we take $B$ below and $A$ on top. It is easy to check that the ordered sum of two orders is an order. One notices immediately, of course, that the resulting ordered sums $A+B$ and $B+A$ are not the same! The order $A+B$ has a greatest element, whereas $B+A$ has two maximal elements. So the ordered sum operation on orders is not commutative. Nevertheless, we shall still call it addition. The operation, which has many useful and interesting features, goes back at least to the 19th century with Cantor, who defined the addition of well orders this way.

Another kind of addition is the ordered sum of two orders $A+B$, which is obtained by placing a copy of $B$ above a copy of $A$, as indicated here by adding the orange copy of $A$ and the yellow copy of $B$. Also shown is the sum $B+A$, with the summands reversed, so that we take $B$ below and $A$ on top. It is easy to check that the ordered sum of two orders is an order. One notices immediately, of course, that the resulting ordered sums $A+B$ and $B+A$ are not the same! The order $A+B$ has a greatest element, whereas $B+A$ has two maximal elements. So the ordered sum operation on orders is not commutative. Nevertheless, we shall still call it addition. The operation, which has many useful and interesting features, goes back at least to the 19th century with Cantor, who defined the addition of well orders this way.

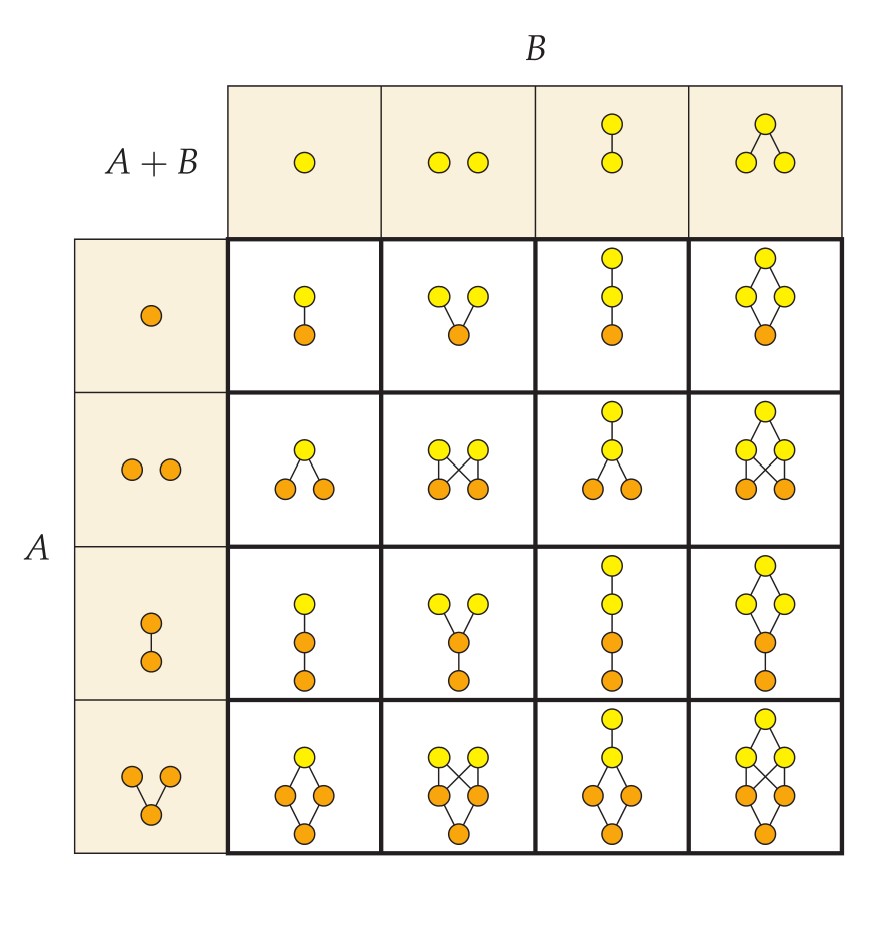

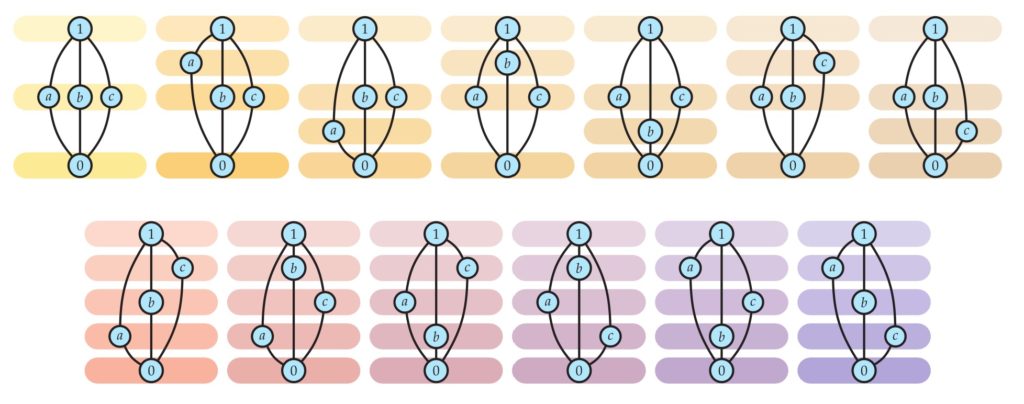

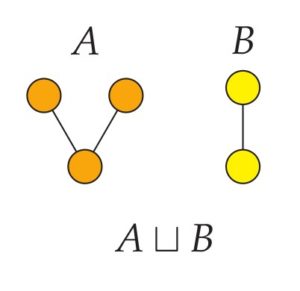

In order to illustrate further examples, I have assembled here an addition table for several simple finite orders. The choices for $A$ appear down the left side and those for $B$ at the top, with the corresponding sum $A+B$ displayed in each cell accordingly.

We can combine the two order addition operations, forming a variety of other orders this way.

The reader is encouraged to explore further how to add various finite orders using these two forms of addition. What is the smallest order that you cannot generate from $1$ using $+$ and $\sqcup$? Please answer in the comments.

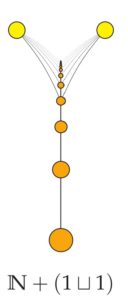

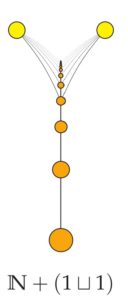

We can also add infinite orders. Displayed here, for example, is the order $\N+(1\sqcup 1)$, the natural numbers wearing two yellow caps. The two yellow nodes at the top form a copy of $1\sqcup 1$, while the natural numbers are the orange nodes below. Every natural number (yes, all infinitely many of them) is below each of the two nodes at the top, which are incomparable to each other. Notice that even though we have Hasse diagrams for each summand order here, there can be no minimal Hasse diagram for the sum, because any particular line from a natural number to the top would be implied via transitivity from higher such lines, and we would need such lines, since they are not implied by the lower lines. So there is no minimal Hasse diagram.

We can also add infinite orders. Displayed here, for example, is the order $\N+(1\sqcup 1)$, the natural numbers wearing two yellow caps. The two yellow nodes at the top form a copy of $1\sqcup 1$, while the natural numbers are the orange nodes below. Every natural number (yes, all infinitely many of them) is below each of the two nodes at the top, which are incomparable to each other. Notice that even though we have Hasse diagrams for each summand order here, there can be no minimal Hasse diagram for the sum, because any particular line from a natural number to the top would be implied via transitivity from higher such lines, and we would need such lines, since they are not implied by the lower lines. So there is no minimal Hasse diagram.

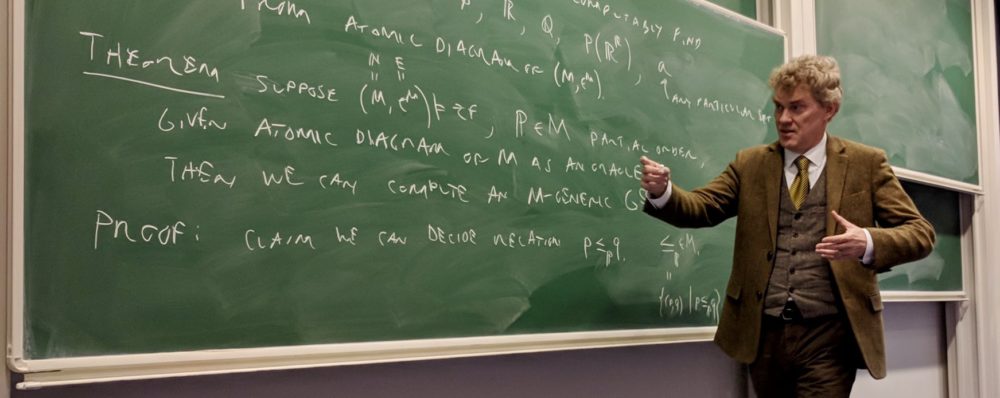

This order happens to illustrate what is called an exact pair, which occurs in an order when a pair of incomparable nodes bounds a chain below, with the property that any node below both members of the pair is below something in the chain. This phenomenon occurs in sometimes unexpected contexts—any countable chain in the hierarchy of Turing degrees in computability theory, for example, admits an exact pair.

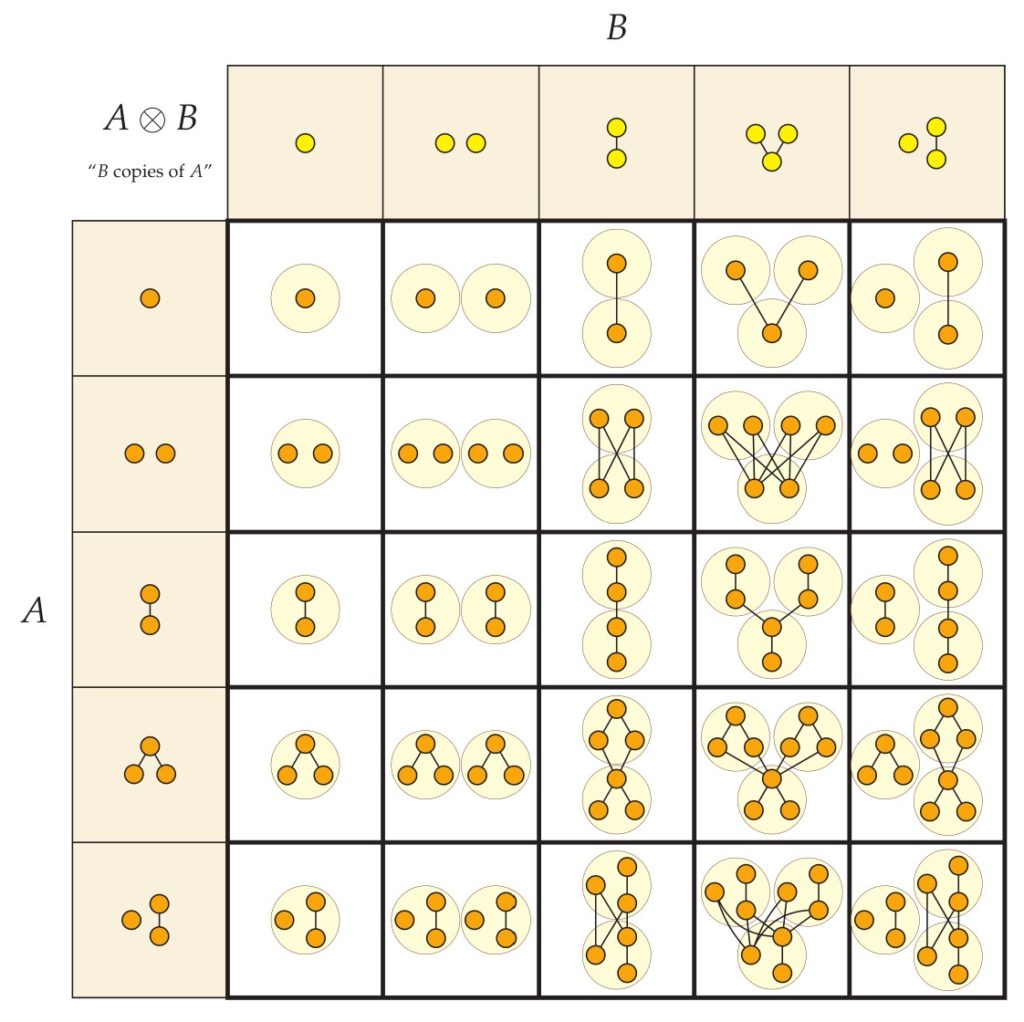

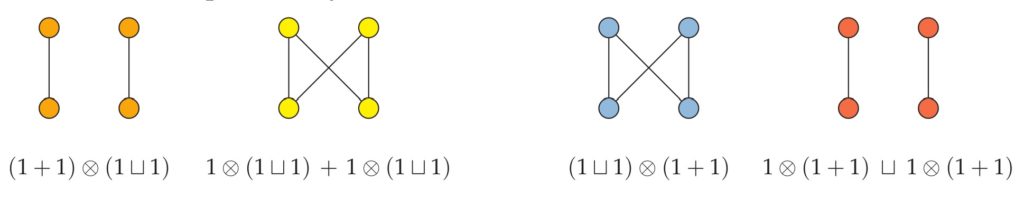

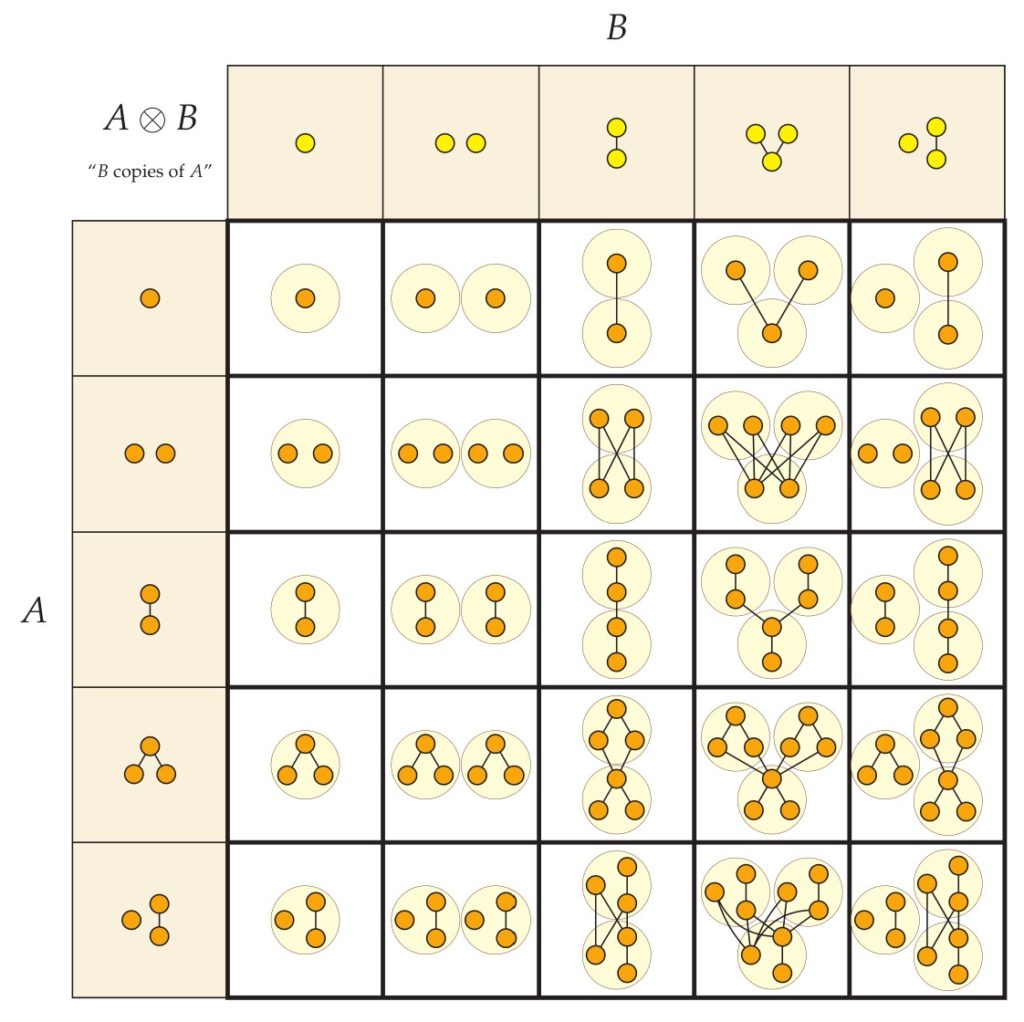

Let us turn now to multiplication. The ordered product $A\otimes B$ is the order resulting from having $B$ many copies of $A$. That is, we replace each node of $B$ with an entire copy of the $A$ order. Within each of these copies of $A$, the order relation is just as in $A$, but the order relation between nodes in different copies of $A$, we follow the $B$ relation. It is not difficult to check that indeed this is an order relation. We can illustrate here with the same two orders we had earlier.

In forming the ordered product $A\otimes B$, in the center here, we take the two yellow nodes of $B$, shown greatly enlarged in the background, and replace them with copies of $A$. So we have ultimately two copies of $A$, one atop the other, just as $B$ has two nodes, one atop the other. We have added the order relations between the lower copy of $A$ and the upper copy, because in $B$ the lower node is related to the upper node. The order $A\otimes B$ consists only of the six orange nodes—the large highlighted yellow nodes of $B$ here serve merely as a helpful indication of how the product is formed and are not in any way part of the product order $A\otimes B$.

Similarly, with $B\otimes A$, at the right, we have the three enlarged orange nodes of $B$ in the background, which have each been replaced with copies of $A$. The nodes of each of the lower copies of $A$ are related to the nodes in the top copy, because in $B$ the two lower nodes are related to the upper node.

I have assembled a small multiplication table here for some simple finite orders.

So far we have given an informal account of how to add and multiply ordered ordered structures. So let us briefly be a little more precise and formal with these matters.

In fact, when it comes to addition, there is a slightly irritating matter in defining what the sums $A\sqcup B$ and $A+B$ are exactly. Specifically, what are the domains? We would like to conceive of the domains of $A\sqcup B$ and $A+B$ simply as the union the domains of $A$ and $B$—we’d like just to throw the two domains together and form the sums order using that combined domain, placing $A$ on the $A$ part and $B$ on the $B$ part (and adding relations from the $A$ to the $B$ part for $A+B$). Indeed, this works fine when the domains of $A$ and $B$ are disjoint, that is, if they have no points in common. But what if the domains of $A$ and $B$ overlap? In this case, we can’t seem to use the union in this straightforward manner. In general, we must disjointify the domains—we take copies of $A$ and $B$, if necessary, on domains that are disjoint, so that we can form the sums $A\sqcup B$ and $A+B$ on the union of those nonoverlapping domains.

What do we mean precisely by “taking a copy” of an ordered structure $A$? This way of talking in mathematics partakes in the philosophy of structuralism. We only care about our mathematical structures up to isomorphism, after all, and so it doesn’t matter which isomorphic copies of $A$ and $B$ we use; the resulting order structures $A\sqcup B$ will be isomorphic, and similarly for $A+B$. In this sense, we are defining the sum orders only up to isomorphism.

Nevertheless, we can be definite about it, if only to verify that indeed there are copies of $A$ and $B$ available with disjoint domains. So let us construct a set-theoretically specific copy of $A$, replacing each individual $a$ in the domain of $A$ with $(a,\text{orange})$, for example, and replacing the elements $b$ in the domain of $B$ with $(b,\text{yellow})$. If “orange” is a specific object distinct from “yellow,” then these new domains will have no points in common, and we can form the disjoint sum $A\sqcup B$ by using the union of these new domains, placing the $A$ order on the orange objects and the $B$ order on the yellow objects.

Although one can use this specific disjointifying construction to define what $A\sqcup B$ and $A+B$ mean as specific structures, I would find it to be a misunderstanding of the construction to take it as a suggestion that set theory is anti-structuralist. Set theorists are generally as structuralist as they come in mathematics, and in light of Dedekind’s categorical account of the natural numbers, one might even find the origin of the philosophy of structuralism in set theory. Rather, the disjointifying construction is part of the general proof that set theory abounds with isomorphic copies of whatever mathematical structure we might have, and this is part of the reason why it serves well as a foundation of mathematics for the structuralist. To be a structuralist means not to care which particular copy one has, to treat one’s mathematical structures as invariant under isomorphism.

But let me mention a certain regrettable consequence of defining the operations by means of a specific such disjointifying construction in the algebra of orders. Namely, it will turn out that neither the disjoint sum operation nor the ordered sum operation, as operations on order structures, are associative. For example, if we use $1$ to represent the one-point order, then $1\sqcup 1$ means the two-point side-by-side order, one orange and one yellow, but really what we mean is that the points of the domain are $\set{(a,\text{orange}),(a,\text{yellow})}$, where the original order is on domain $\set{a}$. The order $(1\sqcup 1)\sqcup 1$ then means that we take an orange copy of that order plus a single yellow point. This will have domain

$$\set{\bigl((a,\text{orange}),\text{orange}\bigr),\bigl((a,\text{yellow}),\text{orange}\bigr),(a,\text{yellow})}$$

The order $1\sqcup(1\sqcup 1)$, in contrast, means that we take a single orange point plus a yellow copy of $1\sqcup 1$, leading to the domain

$$\set{(a,\text{orange}),\bigl((a,\text{orange}),\text{yellow}\bigr),\bigl((a,\text{yellow}),\text{yellow}\bigr)}$$

These domains are not the same! So as order structures, the order $(1\sqcup 1)\sqcup 1$ is not identical with $1\sqcup(1\sqcup 1)$, and therefore the disjoint sum operation is not associative. A similar problem arises with $1+(1+1)$ and $(1+1)+1$.

But not to worry—we are structuralists and care about our orders here only up to isomorphism. Indeed, the two resulting orders are isomorphic as orders, and more generally, $(A\sqcup B)\sqcup C$ is isomorphic to $A\sqcup(B\sqcup C)$ for any orders $A$, $B$, and $C$, and similarly with $A+(B+C)\cong(A+B)+C$, as discussed with the theorem below. Furthermore, the order isomorphism relation is a congruence with respect to the arithmetic we have defined, which means that $A\sqcup B$ is isomorphic to $A’\sqcup B’$ whenever $A$ and $B$ are respectively isomorphic to $A’$ and $B’$, and similarly with $A+B$ and $A\otimes B$. Consequently, we can view these operations as associative, if we simply view them not as operations on the order structures themselves, but on their order-types, that is, on their isomorphism classes. This simple abstract switch in perspective restores the desired associativity. In light of this, we are free to omit the parentheses and write $A\sqcup B\sqcup C$ and $A+B+C$, if care about our orders only up to isomorphism. Let us therefore adopt this structuralist perspective for the rest of our treatment of the algebra of orders.

Let us give a more precise formal definition of $A\otimes B$, which requires no disjointification. Specifically, the domain is the set of pairs $\set{(a,b)\mid a\in A, b\in B}$, and the order is defined by $(a,b)\leq_{A\otimes B}(a’,b’)$ if and only if $b\leq_B b’$, or $b=b’$ and $a\leq_A a’$. This order is known as the reverse lexical order, since we are ordering the nodes in the dictionary manner, except starting from the right letter first rather than the left as in an ordinary dictionary. One could of course have defined the product using the lexical order instead of the reverse lexical order, and this would give $A\otimes B$ the meaning of “$A$ copies of $B$.” This would be a fine alternative and in my experience mathematicians who rediscover the ordered product on their own often tend to use the lexical order, which is natural in some respects. Nevertheless, there is a huge literature with more than a century of established usage with the reverse lexical order, from the time of Cantor, who defined ordinal multiplication $\alpha\beta$ as $\beta$ copies of $\alpha$. For this reason, it seems best to stick with the reverse lexical order and the accompanying idea that $A\otimes B$ means “$B$ copies of $A$.” Note also that with the reverse lexical order, we shall be able to prove left distributivity $A\otimes(B+C)=A\otimes B+A\otimes C$, whereas with the lexical order, one will instead have right distributivity $(B+C)\otimes^* A=B\otimes^* A+C\otimes^* A$.

Let us begin to prove some basic facts about the algebra of orders.

Theorem. The following identities hold for orders $A$, $B$, and $C$.

- Associativity of disjoint sum, ordered sum, and ordered product.\begin{eqnarray*}A\sqcup(B\sqcup C) &\iso& (A\sqcup B)\sqcup C\\ A+(B+C) &\iso& (A+B)+C\\ A\otimes(B\otimes C) &\iso& (A\otimes B)\otimes C \end{eqnarray*}

- Left distributivity of product over disjoint sum and ordered sum.\begin{eqnarray*} A\otimes(B\sqcup C) &\iso& (A\otimes B)\sqcup(A\otimes C)\\ A\otimes(B+C) &\iso& (A\otimes B)+(A\otimes C) \end{eqnarray*}

In each case, these identities are clear from the informal intended meaning of the orders. For example, $A+(B+C)$ is the order resulting from having a copy of $A$, and above it a copy of $B+C$, which is a copy of $B$ and a copy of $C$ above it. So one has altogether a copy of $A$, with a copy of $B$ above that and a copy of $C$ on top. And this is the same as $(A+B)+C$, so they are isomorphic.

One can also aspire to give a detailed formal proof verifying that our color-coded disjointifying process works as desired, and the reader is encouraged to do so as an exercise. To my way of thinking, however, such a proof offers little in the way of mathematical insight into algebra of orders. Rather, it is about checking the fine print of our disjointifying process and making sure that things work as we expect. Several of the arguments can be described as parenthesis-rearranging arguments—one extracts the desired information from the structure of the domain order and puts that exact same information into the correct form for the target order.

For example, if we have used the color-scheme disjointifying process described above, then the elements of $A\sqcup(B\sqcup C)$ each have one of the following forms, where $a\in A$, $b\in B$, and $c\in C$:

$$(a,\text{orange})$$

$$\bigl((b,\text{orange}),\text{yellow}\bigr)$$

$$\bigl((c,\text{yellow}),\text{yellow}\bigr)$$

We can define the color-and-parenthesis-rearranging function $\pi$ to put them into the right form for $(A\sqcup B)\sqcup C$ as follows:

\begin{align*}

\pi:(a,\text{orange})\quad&\mapsto\quad \bigl((a,\text{orange}),\text{orange}\bigl) \\

\pi:\bigl((b,\text{orange}),\text{yellow}\bigr)\quad&\mapsto\quad \bigl((b,\text{yellow}),\text{orange}\bigl) \\

\pi:\bigl((c,\text{yellow}),\text{yellow}\bigr)\quad&\mapsto\quad (c,\text{yellow})

\end{align*}

In each case, we will preserve the order, and since the orders are side-by-side, the cases never interact in the order, and so this is an isomorphism.

Similarly, for distributivity, the elements of $A\otimes(B\sqcup C)$ have the two forms:

$$\bigl(a,(b,\text{orange})\bigr)$$

$$\bigl(a,(c,\text{yellow})\bigr)$$

where $a\in A$, $b\in B$, and $c\in C$. Again we can define the desired ismorphism $\tau$ by putting these into the right form for $(A\otimes B)\sqcup(A\otimes C)$ as follows:

\begin{align*}

\tau:\bigl(a,(b,\text{orange})\bigr)\quad&\mapsto\quad \bigl((a,b),\text{orange}\bigr) \\

\tau:\bigl(a,(c,\text{yellow})\bigr)\quad&\mapsto\quad\bigl((a,c),\text{yellow}\bigr)

\end{align*}

And again, this is an isomorphism, as desired.

Since order multiplication is not commutative, it is natural to inquire about the right-sided distributivity laws:

\begin{eqnarray*}

(B+C)\otimes A&\overset{?}{\cong}&(B\otimes A)+(C\otimes A)\\

(B\sqcup C)\otimes A&\overset{?}{\cong}&(B\otimes A)\sqcup(C\otimes A)

\end{eqnarray*}

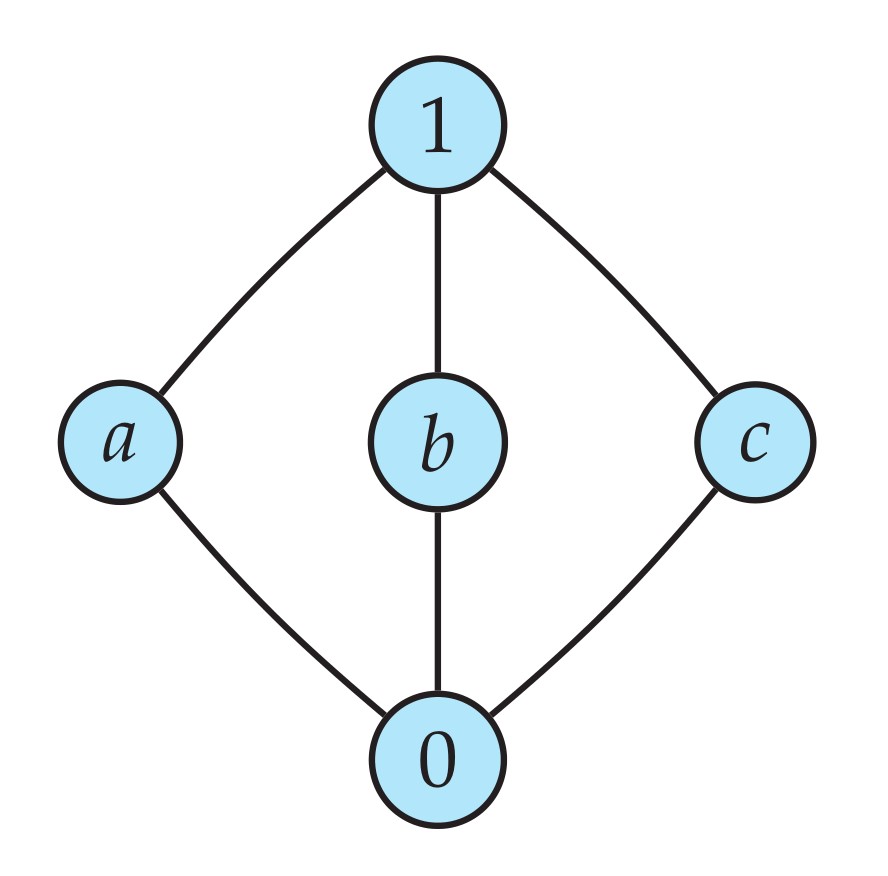

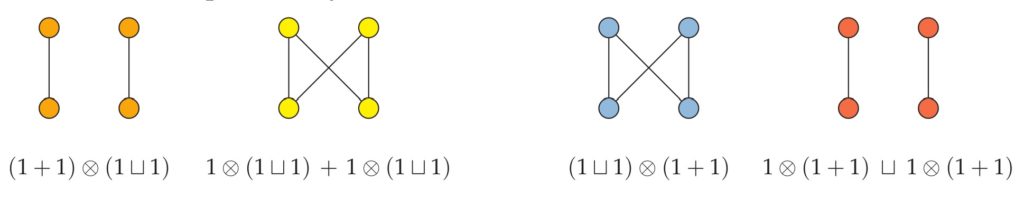

Unfortunately, however, these do not hold in general, and the following instances are counterexamples. Can you see what to take as $A$, $B$, and $C$? Please answer in the comments.

Theorem.

- If $A$ and $B$ are linear orders, then so are $A+B$ and $A\otimes B$.

- If $A$ and $B$ are nontrivial linear orders and both are endless, then $A+B$ is endless; if at least one of them is endless, then $A\otimes B$ is endless.

- If $A$ is an endless dense linear order and $B$ is linear, then $A\otimes B$ is an endless dense linear order.

- If $A$ is an endless discrete linear order and $B$ is linear, then $A\otimes B$ is an endless discrete linear order.

Proof. If both $A$ and $B$ are linear orders, then it is clear that $A+B$ is linear. Any two points within the $A$ copy are comparable, and any two points within the $B$ copy, and every point in the $A$ copy is below any point in the $B$ copy. So any two points are comparable and thus we have a linear order. With the product $A\otimes B$, we have $B$ many copies of $A$, and this is linear since any two points within one copy of $A$ are comparable, and otherwise they come from different copies, which are then comparable since $B$ is linear. So $A\otimes B$ is linear.

For statement (2), we know that $A+B$ and $A\otimes B$ are nontrivial linear orders. If both $A$ and $B$ are endless, then clearly $A+B$ is endless, since every node in $A$ has something below it and every node in $B$ has something above it. For the product $A\otimes B$, if $A$ is endless, then every node in any copy of $A$ has nodes above and below it, and so this will be true in $A\otimes B$; and if $B$ is endless, then there will always be higher and lower copies of $A$ to consider, so again $A\otimes B$ is endless, as desired.

For statement (3), assume that $A$ is an endless dense linear and that $B$ is linear. We know from (1) that $A\otimes B$ is a linear order. Suppose that $x<y$ in this order. If $x$ and $y$ live in the same copy of $A$, then there is a node $z$ between them, because $A$ is dense. If $x$ occurs in one copy of $A$ and $B$ in another, then because $A$ is endless, there will a node $z$ above $x$ in its same copy, leading to $x<z<y$ as desired. (Note: we don’t need $B$ to be dense.)

For statement (4), assume instead that $A$ is an endless discrete linear order and $B$ is linear. We know that $A\otimes B$ is a linear order. Every node of $A\otimes B$ lives in a copy of $A$, where it has an immediate successor and an immediate predecessor, and these are also immediate successor and predecessor in $A\otimes B$. From this, it follows also that $A\otimes B$ is endless, and so it is an endless discrete linear order. $\Box$

The reader is encouraged to consider as an exercise whether one can drop the “endless” hypotheses in the theorem. Please answer in the comments.

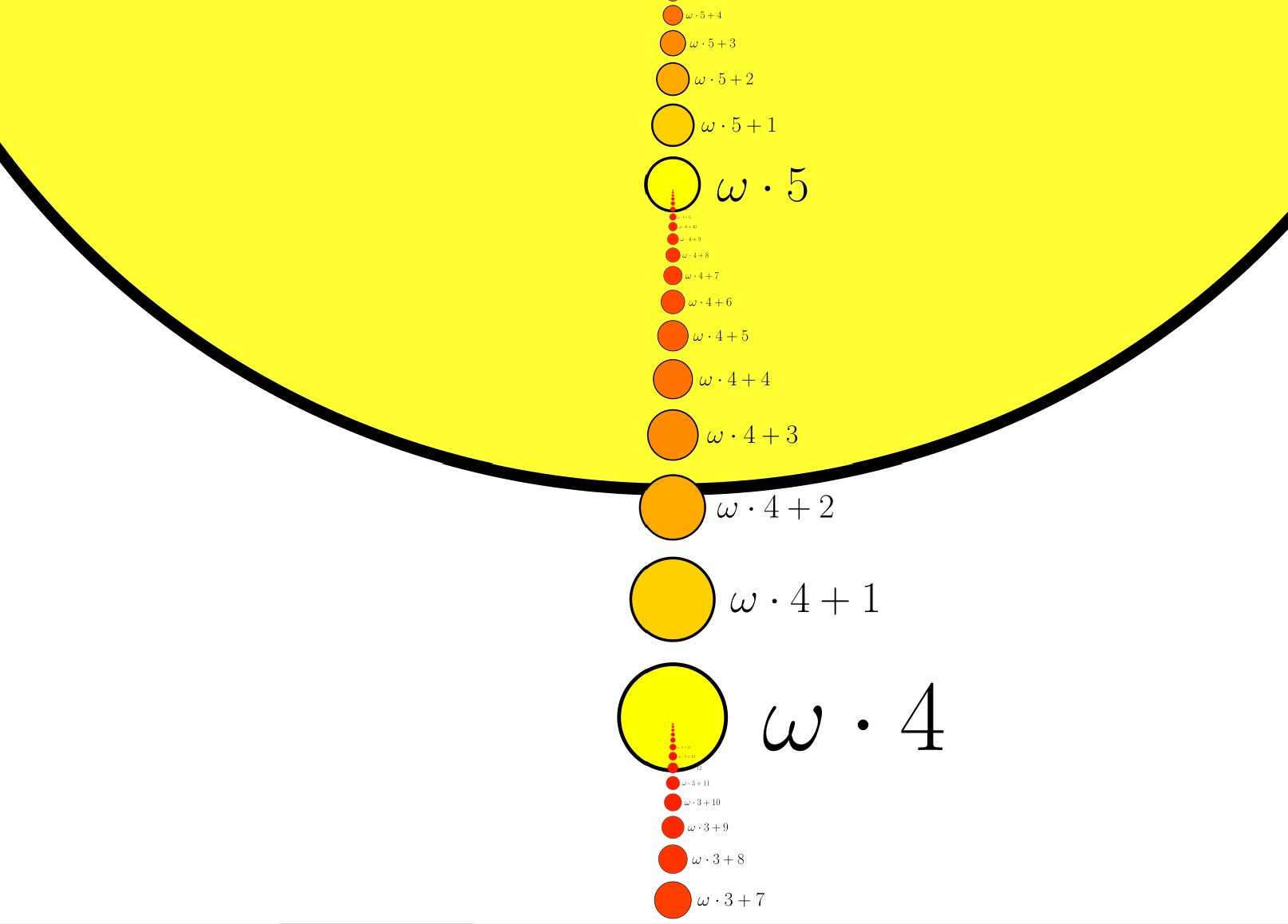

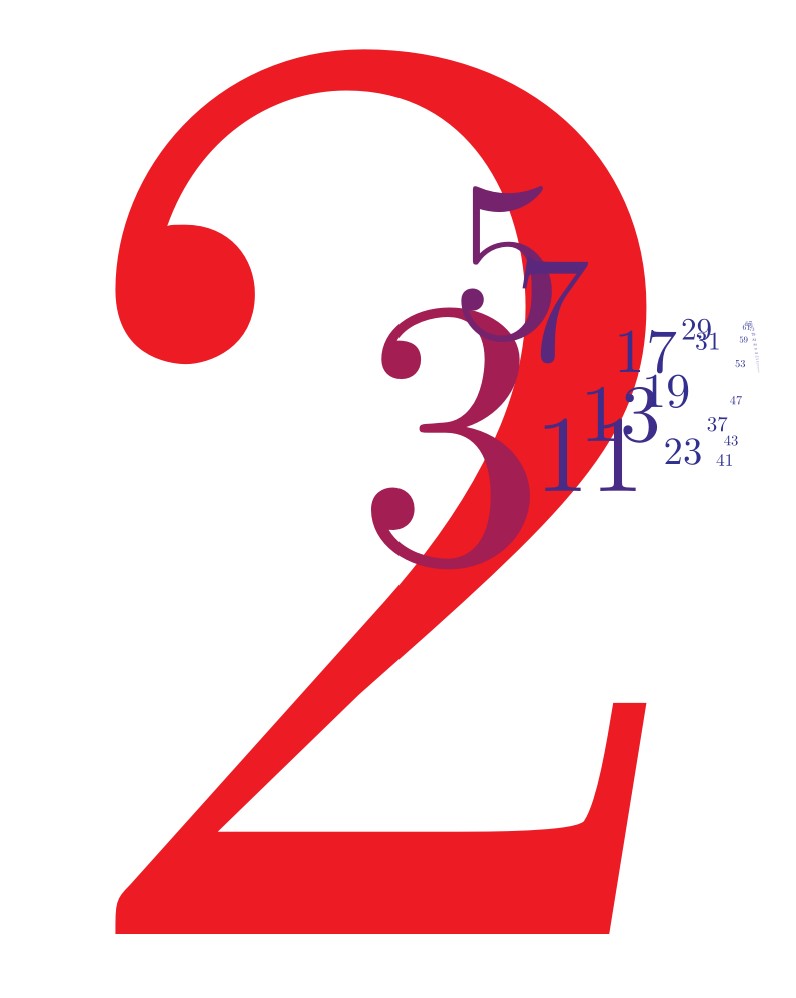

Theorem. The endless discrete linear orders are exactly those of the form $\Z\otimes L$ for some linear order $L$.

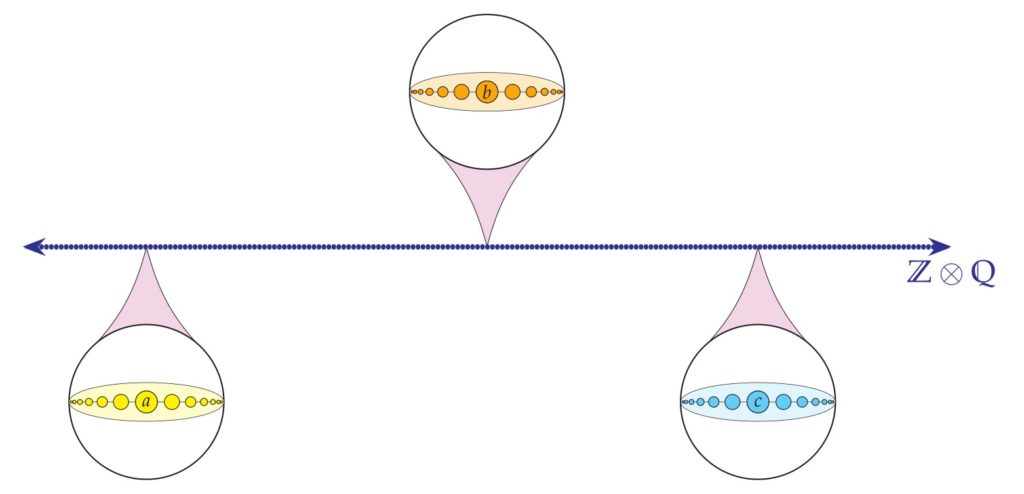

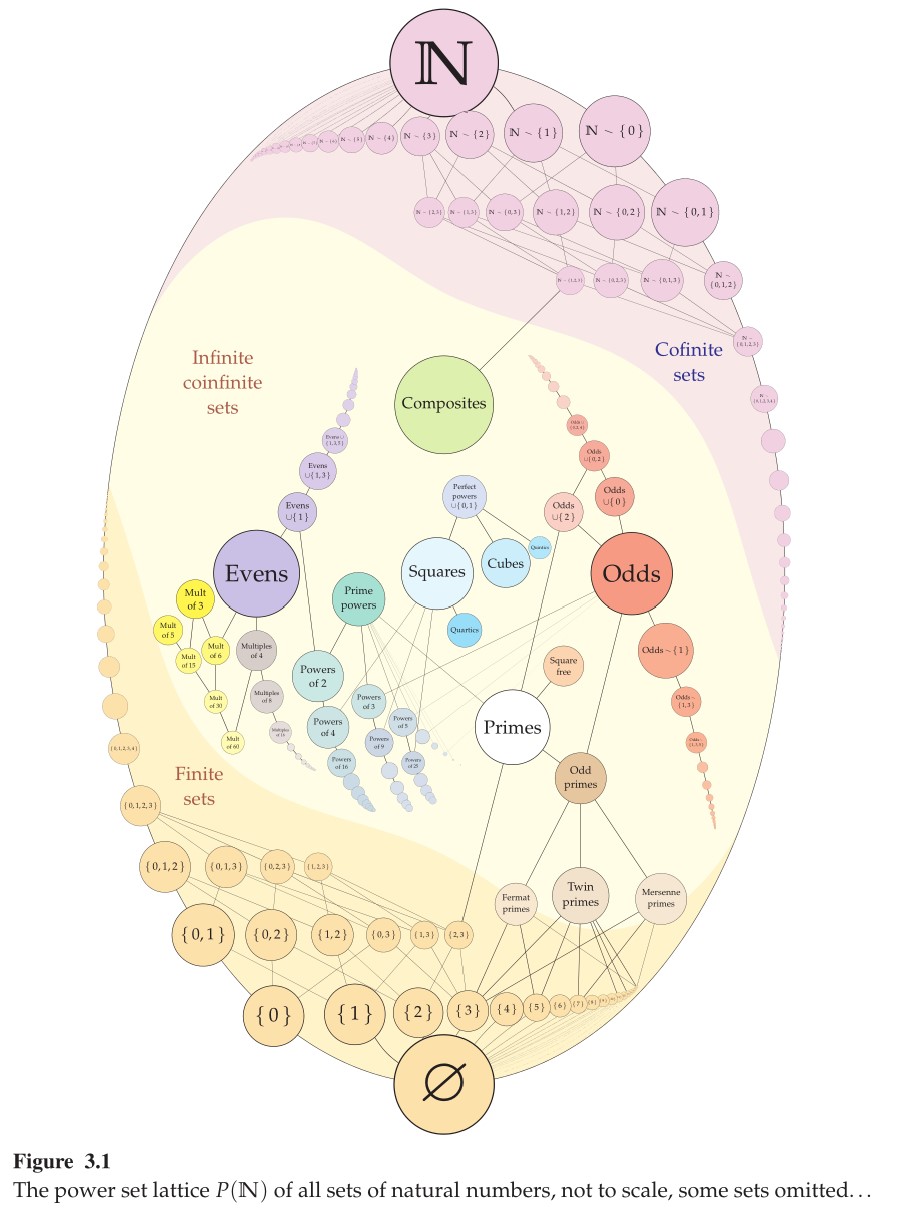

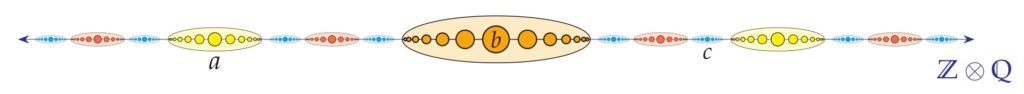

Proof. If $L$ is a linear order, then $\Z\otimes L$ is an endless discrete linear order by the theorem above, statement (4). So any order of this form has the desired feature. Conversely, suppose that $\P$ is an endless discrete linear order. Define an equivalence relation for points in this order by which $p\sim q$ if and only $p$ and $q$ are at finite distance, in the sense that there are only finitely many points between them. This relation is easily seen to be reflexive, transitive and symmetric, and so it is an equivalence relation. Since $\P$ is an endless discrete linear order, every object in the order has an immediate successor and immediate predecessor, which remain $\sim$-equivalent, and from this it follows that the equivalence classes are each ordered like the integers $\Z$, as indicated by the figure here.

The equivalence classes amount to a partition of $\P$ into disjoint segments of order type $\Z$, as in the various colored sections of the figure. Let $L$ be the induced order on the equivalence classes. That is, the domain of $L$ consists of the equivalence classes $\P/\sim$, which are each a $\Z$ chain in the original order, and we say $[a]<_L[b]$ just in case $a<_{\P}b$. This is a linear order on the equivalence classes. And since $\P$ is $L$ copies of its equivalence classes, each of which is ordered like $\Z$, it follows that $\P$ is isomorphic to $\Z\otimes L$, as desired. $\Box$

(Interested readers are advised that the argument above uses the axiom of choice, since in order to assemble the isomorphism of $\P$ with $\Z\otimes L$, we need in effect to choose a center point for each equivalence class.)

If we consider the integers inside the rational order $\Z\of\Q$, it is clear that we can have a discrete suborder of a dense linear order. How about a dense suborder of a discrete linear order?

Question. Is there a discrete linear order with a suborder that is a dense linear order?

What? How could that happen? In my experience, mathematicians first coming to this topic often respond instinctively that this should be impossible. I have seen sophisticated mathematicians make such a pronouncement when I asked the audience about it in a public lecture. The fundamental nature of a discrete order, after all, is completely at odds with density, since in a discrete order, there is a next point up and down, and a next next point, and so on, and this is incompatible with density.

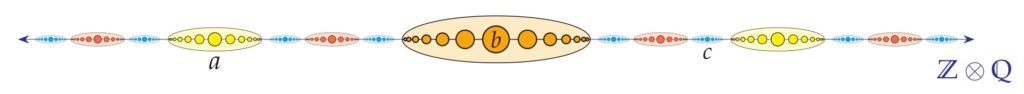

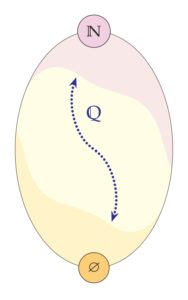

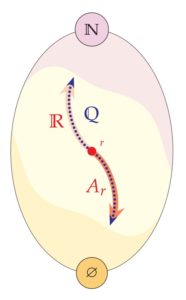

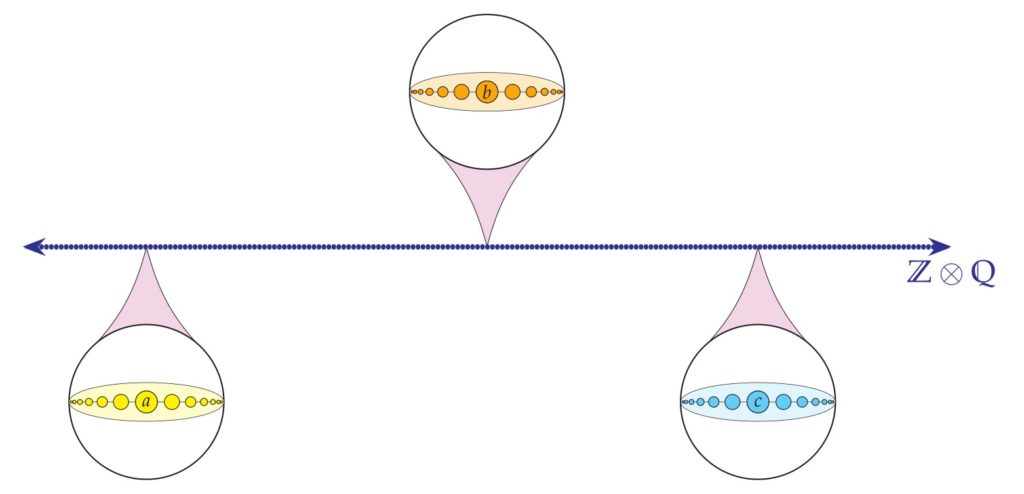

Yet, surprisingly, the answer is Yes! It is possible—there is a discrete order with a suborder that is densely ordered. Consider the extremely interesting order $\Z\otimes\Q$, which consists of $\Q$ many copies of $\Z$, laid out here increasing from left to right. Each tiny blue dot is a rational number, which has been replaced with an entire copy of the integers, as you can see in the magnified images at $a$, $b$, and $c$.

The order is quite subtle, and so let me also provide an alternative presentation of it. We have many copies of $\Z$, and those copies are densely ordered like $\Q$, so that between any two copies of $\Z$ is another one, like this:

Perhaps it helps to imagine that the copies of $\Z$ are getting smaller and smaller as you squeeze them in between the larger copies. But you can indeed always fit another copy of $\Z$ between, while leaving room for the further even tinier copies of $\Z$ to come.

The order $\Z\otimes\Q$ is discrete, in light of the theorem characterizing discrete linear orders. But also, this is clear, since every point of $\Z\otimes\Q$ lives in its local copy of $\Z$, and so has an immediate successor and predecessor there. Meanwhile, if we select exactly one point from each copy of $\Z$, the $0$ of each copy, say, then these points are ordered like $\Q$, which is dense. Thus, we have proved:

Theorem. The order $\Z\otimes\Q$ is a discrete linear order having a dense linear order as a suborder.

One might be curious now about the order $\Q\otimes\Z$, which is $\Z$ many copies of $\Q$. This order, however, is a countable endless dense linear order, and therefore is isomorphic to $\Q$ itself.

This material is adapted from my book-in-progress, Topics in Logic, drawn from Chapter 3 on Relational Logic, which incudes an extensive section on order theory, of which this is an important summative part.