Let me dive right in with the main puzzle.

Main puzzle. You are a contestant on a game show, known for having perfectly logical contestants. There is another contestant, whom you’ve never met, but whom you can count on to be perfectly logical, just as logical as you are.

The game is cooperative, so either you will both win or both lose, together. Imagine the stakes are very high—perhaps life and death. You and your partner are separated from one another, in different rooms. The game proceeds in turns—round 1, round 2, round 3, as many as desired to implement your strategy.

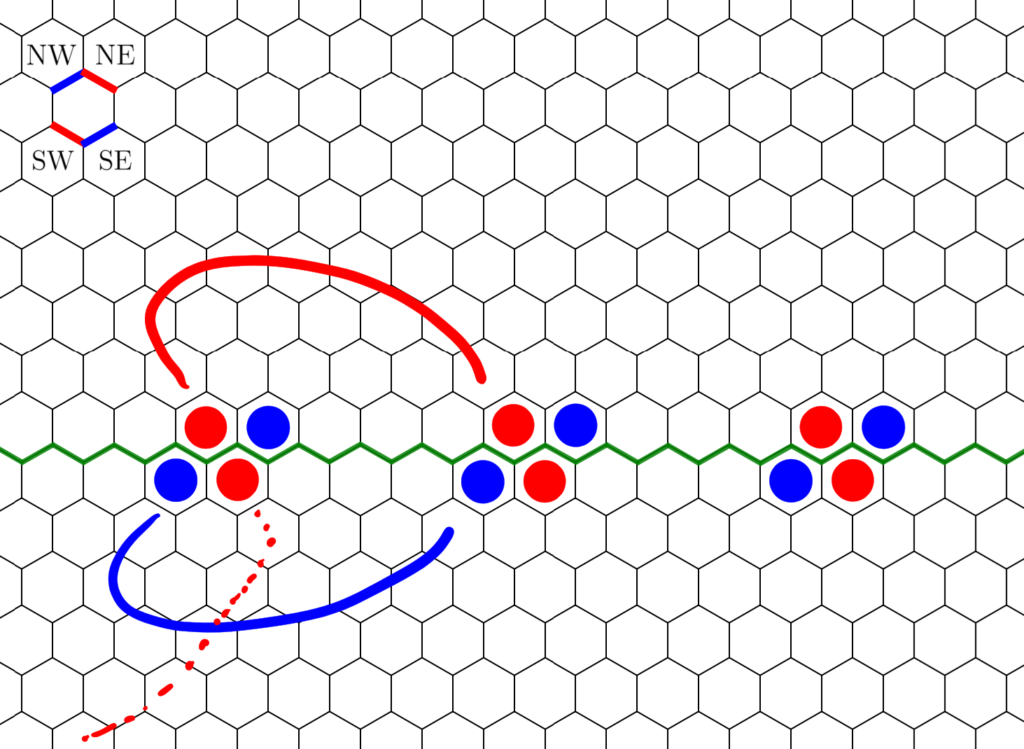

On each round, each contestant may choose either to end the game and announce a color (any color) to the game host or to send a message (any kind of message) to their partner contestant, to be received before the next round. Messages are sent simultaneously, crossing in transit.

You win the game if on some round both players opt to end the game and announce a color to the host and furthermore they do so with exactly the same color. That is, you win if you both halt the game on the same round with the same color. lf only one player announces a color, or if both do but the colors don’t match, then the game is over, but you have lost.

Round 1 is about to begin. What do you do?

Before getting to solutions, I should also like to mention several variations of the puzzle.

Alternation variation. In this variation of the puzzle, the contestants alternate in their right to send messages—only contestant 1 can send on round 1, then contestant 2 on round 2 and so forth, but still they aim to announce the same color on a round. You are contestant 1—what do you do?

Collision variation. In this variation, players may opt on each round either to end the game and announce a color, to send a message, or to do nothing. But the new thing is that if both players opt to send a message, then the messages collide and are not delivered, although an error message is generated (so the players know what happened). What do you do?

Pigeon variation. This version is like the alternating turn variation, except that now the contestants are separated at much greater distance, and the messages are sent by carrier pigeon, so neither can be sure that the messages actually arrive. You are contestant 1—what do you do?

Post your solutions in the comments! Please do so before reading the rest of this post, and then come back to read more. There are lively discussions occuring on the Twitter thread about this puzzle, on Hacker News, on www.reddit/r/mathriddles, and on www.reddit/r/philosophy.

—————————–

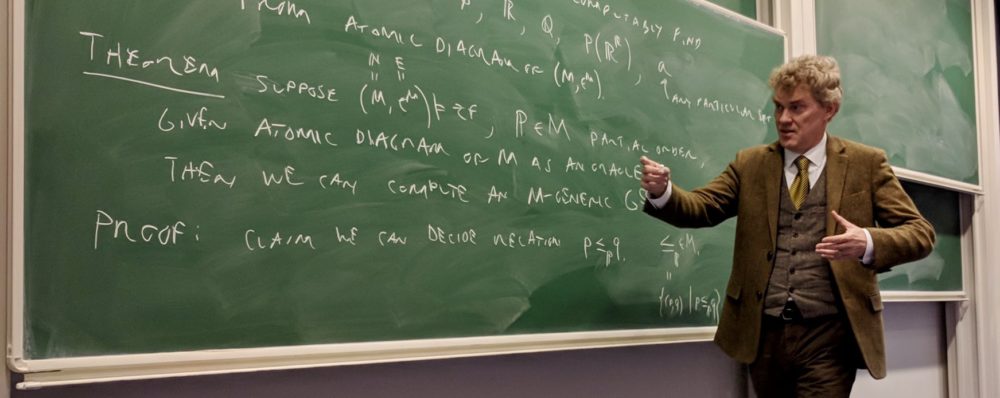

We had used these puzzles in our admissions interviews of candidates for a place at Oxford University in the degree courses Math/philosophy, CS/philosophy, and PPE at University College, Oxford. The candidates were high-school students, mostly 17 years old, having made the interview shortlist on the basis of the rest of their applications, including A-level scores, university entrance exam, essay, and recommendations (all considered in light of relative advantage/disadvantage). The interviews were an in-depth back-and-forth discussion, as much as could be had in about 25 minutes. These interviews, of course, are just one component among many in regard to the difficult admissions decision, a chance for the candidate to show us how they think through a problem, how well they can explain their ideas, how well they take hints and suggestions. In every interview, we had paused at a certain stage, when the candidate had a fully formed argument for one of the variations, and asked them to undertake an integrative exercise, summarizing as clearly as they could the entire problem and solution and how they expected it to play out. Since these were interviews for joint philosophy degrees, in my view this step was a key part of the interview, measuring the ability of the candidate to integrate what they had learned from the discussion and to present a complete, coherent argument.

Several of these puzzles are rather open-ended, not necessarily with a clear-cut objectively correct answer, although there are certain important issues that arise and that we had hoped the candidates would realize. So let me now discuss the puzzles in detail and the aspects of them that I find interesting.

For the main puzzle, it seems clear that one should not announce a color to the host straight away in round 1, because it seems not likely enough that the other contestant would also do so with exactly the same color. Rather, one should use the messaging capability somehow to agree on the color and round number on which to end the game. We should only announce, if we have both clearly expressed a plan to announce a specific color on a specific round.

At first, it might seem reasonable to send a message along the lines of “Let’s both announce red on round 3; please confirm in round 2.” The hope would be that the other player would indeed confirm on round 2, and then both would announce the final color of red on round 3.

That idea would work, if we were taking turns in sending messages, as in the alternation version of the puzzle. But in the main puzzle, the players are sending their messages simultaneously, and there is a difficulty for the previous proposal that can be realized by considering what kind of message we might expect to be receiving from our partner on round 1. Namely, perhaps they had a similar idea. It would be a lucky case indeed, if they had had exactly the same idea, also proposing to announce red in round 3. In that event, we would both confirm in round 2 and win with red in round 3.

But a more problematic case would occur if our partner had had a very similar idea, but happened to have made the proposal with a different color. Perhaps in round 1 our partner would have sent the message, “Let’s both announce blue on round 3; please confirm in round 2.” What shall we do then in round 2? If I decide to try to stick with my original red color, I might say, “Let’s use red in round 3”, then the other player might similarly decide to stick with blue, and we would still be at an impasse. Alternatively, if I decide to defer and switch to blue, perhaps they also defer and switch to red. What is clear is that we can’t be sure of confirming on the same color in round 2, and clearly we shouldn’t announce in round 3 with the color choice still unsettled. So the procedure we have discussed so far seems unsuitable.

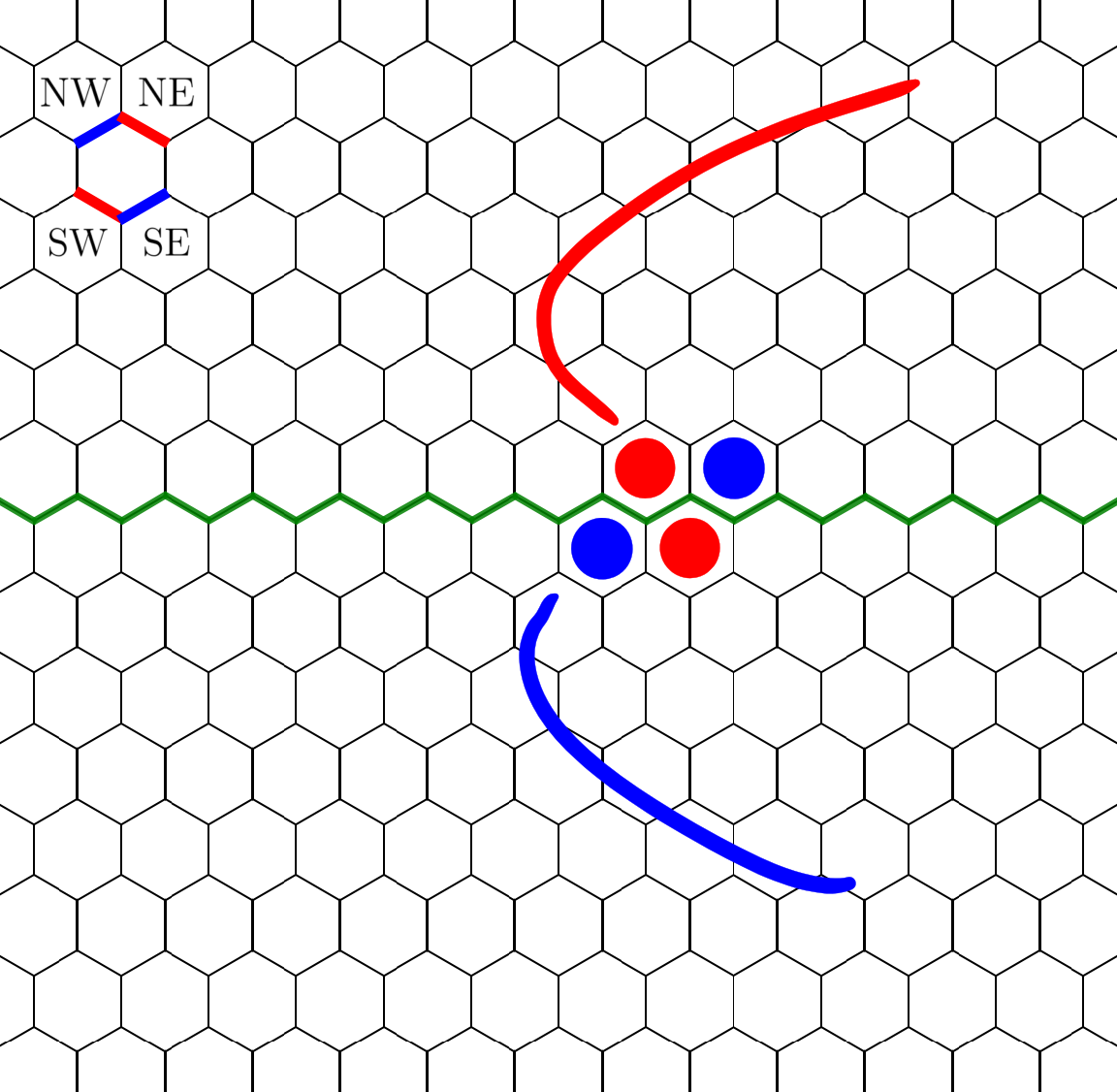

A deeper contemplation of the problem reveals that this issue of the other contestant doing something very similar, but perhaps with a different color, is a fundamental obstacle to many solution attempts. There is a fundamental symmetry in play between the contestants. Since the messages are sent and received at the same time, and both players are equally logical, it could be that we both end up sending the same kind of message each time, except with different colors. We need somehow to agree on a color and a round number, but it seems that however we decide to make a proposal, it would be equally logical for our partner to make a similar proposal, but with colors permuted somehow.

We seem to need to break the symmetry somehow. Perhaps one might hope to use the alphabetically least color, amongst the two colors that have been proposed so far. That would seem to be a perfectly reasonable way to break the symmetry. But the problem here is that there are also many other perfectly reasonable ways to break the symmetry—the shortest wavelength color, the shorter color word, the color proposed by the younger person, by the older person, and so on. The difficulty is that any given proposal might be faced with a similar but equally reasonable proposal about how to break the symmetry. If I had proposed one such criterion, perhaps my partner proposes another, and we haven’t made any progress, but rather only replaced the difficulty of agreeing on the color with the difficulty of agreeing on the decision criterion of how to decide.

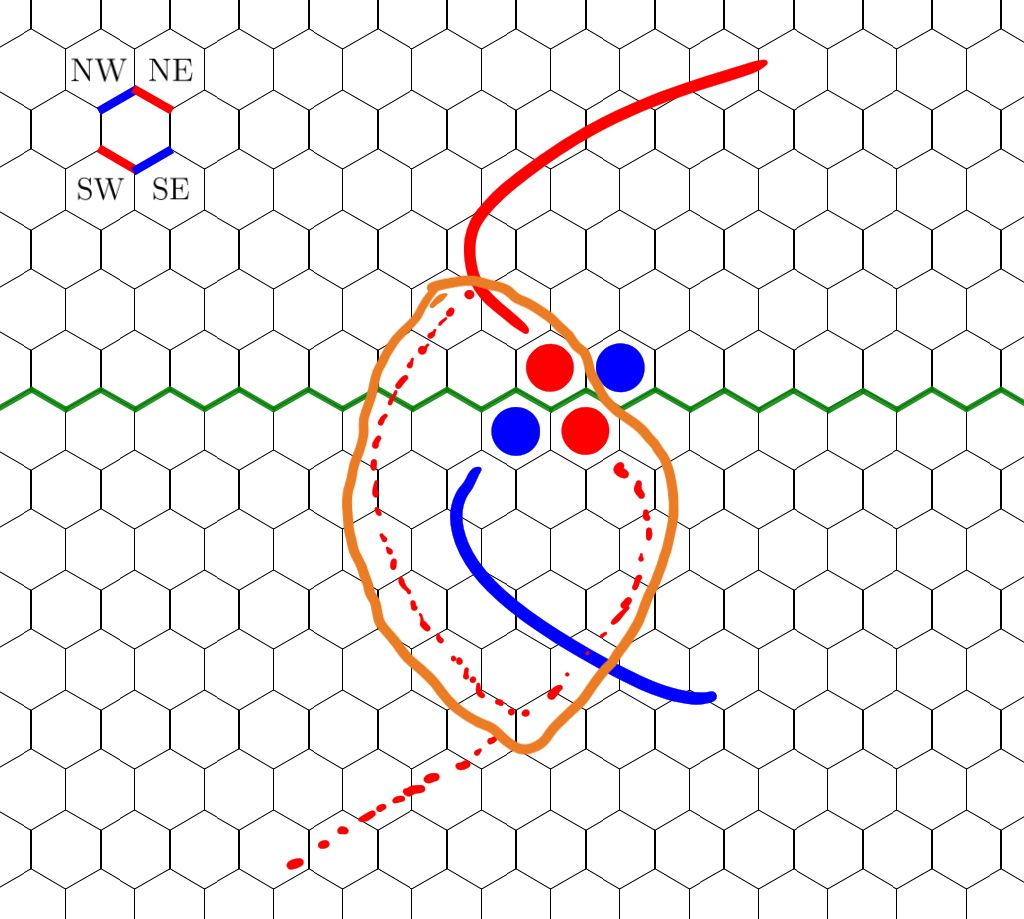

A key insight comes with the idea to use randomness. Suppose I had said in round 1, “I suggest we both announce red next round; I shall do so, if you also suggest this,” but you had said, “I suggest we both announce blue next round; I shall do so, if you also suggest this.” But I have got a coin in my pocket, and from now on, I intend each round to flip the coin, sending the red message on heads and the blue message on tails. If you do likewise, then we are very likely in a few rounds to hit upon the same message, and then we shall win on the next round by following through, announcing the agreed-upon color. That is, if in the first round we each happen to mention a color (whether or not my partner’s message was of the specific form I had mentioned), then I am going on every round to send a message as above, but using one of the two colors randomly. If you logically also choose to do this, then we are very likely to happen to choose the same color on some round eventually, and then win on the following round. This randomzing strategy thus seems fairly sound as a means to come to agreement, and if the partner also realizes this we should expect to win quickly, in just a few rounds with high likelihood. For this reason, I find this to be the best strategy.

A slightly more abstract way to describe the strategy I am proposing is that the symmetry between the players will need to be broken by us agreeing which of us will be leading the process and which of us will follow. I can flip a coin each round to decide if I should try to be leader or follower on that round. On heads, I shall propose a specific plan, “let’s say red next round, if your message indicates that you will follow my suggestion.” On tails, I shall send a message saying, “I am going to follow your plan of action, if you send one this round.” In this way, we are likely in a few rounds to have established a leader and follower, and win shortly afterward.

Some student candidates and commentators had proposed an interesting idea of trying to blend the two colors. This would be a way of coming to an agreement, but without needing to break the symmetry between the players. If I had proposed initially that we should announce red and you had proposed blue, then the idea is that logically we should both try to average these colors and say purple. I like this idea a lot, but it seems problematic in light of the fact that we don’t have such a clear and unambiguous means of combining colors. For example, should we mix the colors in the manner of mixing paint or rather in the manner of mixing colored light, which produces completely different results? Even when mixing red+blue, I might say purple and you might say violet. And what of stranger color combinations, such as orange+green? If we were using rgb colors, then some colors are simply adjacent in the color space (or an even distance away), and so they have no exact average mixing. Furthermore, why should we use rgb rather than cmyk or another color space system? And color mixing does not work identically for these two systems. For these reasons, I find the color mixing idea ultimately less than completely successful.

The alternation variation of the puzzle admits an easy solution, since the symmetry is broken already by the rules of the game. Player 1 will be the first to send a message, and can simply say, “I shall announce red on round 2; if you do so as well then we shall win.” There would be no reason for player 2 not to follow along, and so the players can expect to win on round 2.

Some candidates had suggested a confirmation round, having player 1 say, “let’s say red on round 3, confirm if that is agreeable.” Then both players would confirm the intention on round 2, and win on round 3. This is also successful, but it seems to me that the confirmation step is not strictly needed.

The collision variation is an interesting hybrid, because although there is a symmetry between the players in terms of how the rules apply to them, the symmetry is broken in the event that one sends a message and the other does not. The best solution here seems to be a random solution. Namely, flip a coin to decide whether to send a message or stay silent. On heads, send the message “Announce red on next round, if this message gets through.” On tails, do nothing, and plan to follow whatever is suggested on the message that might be received. Because of the randomness, it is very likely that in a few rounds a message gets through one way or the other, with a quick win straight afterward.

The pigeon variation is simply a version of the two-generals problem. The first player can try to propose a specific plan, naming a round and color, and ask for confirmation. But the confirmation itself will need to be confirmed, if the other player is to want certainty. But in this case the confirmation of the confirmation will need to be confirmed, and so on ad infinitum. No finite number of confirmations of receipt will be enough, even if all are received, since if $n$ confirmations suffice to attain mutual certainty, then the last confirmation needn’t be sent, since the protocol would work even if it didn’t arrive, and so $n-1$ should also suffice, a contradiction.

Meanwhile, one can attain very high degree of confidence in the plan. If on round 1 the first player sends the message, “We shall say red on round 1000, please confirm,” then he might hope it gets through and confirmation received. On each subsequent round, he should send this message again, together with a complete record of all prior messages sent/received. Player 2, if receiving the message on round 1 should simply follow along and send confirmations; but if nothing was received on round 1, he should not start a competing plan, which would only reintroduce the priority issue of the main puzzle, since the symmetry is already clearly broken for this version with player 1 in the leading role. So if no message was received, player 2 should simply reply with “sorry, no message received; please resend.” Eventually, messages are likely to get through and the two players will be on track to win with high probability. The players should plan on announcing red on round 1000 according to the plan, even if confirmations are missed. One can increase the probability by increasing round 1000 to a much higher number, presuming that the players can keep careful track of the round numbers. It would seem to be a mistake ever to try to change the round number or the color after some messages are sent, since perhaps the originals were received and only the cofirmations were missed, and there would be abundant confusion to have two or more plans in play.

In the admissions interviews, which were generally less than 25 minutes, we were happy if a candidate got to the realization of the symmetry issue in the main puzzle, before going on to the alternating version, which most students got quickly, and then the collision version, where the randomness idea seemed to arise more naturally. The best candidates were then able to realize how to apply the randomness idea to the main version. With the pigeon version of the puzzle, successful candidates realized the need to achieve confirmation and confirmation of confirmation, and a few put this together to mount the impossibility argument for the case of certainty, and most realized how to increase the likelihood of success by picking a distant round and repeating messages. It was quite enjoyable for me to discuss these problems with so many very sharp student candidates.

Let me close by mentioning a few observations that surprised me about using the puzzles in an interview setting.

The first observation is the remarkable amount of personality that was revealed by the candidate’s choices in the puzzles. Some candidates tended to follow what might be called a leader’s approach (or the bully strategy?), attempting in the main puzzle to achieve agreement by conveying obstinateness in the color choice, to convince the other person to change sides as a way of coming to agreement. An equal number of other candidates tried instead to be deferential, sending messages that they would agree to use whichever color the other person wanted. Of course, each of these strategies works fine when paired with the other, but when paired with exactly the same personality, the methods face the symmetry problem we discussed earlier. Some brilliant candidates pointed out that the role that these personality differences played in the puzzle—it was very unlikely that the two contestants would be perfectly balanced in their personalities, and so the symmetry would be broken simply because one candidate would be slightly more insistent or slightly more deferential. And I have to say that realistically, this is how the puzzle would actually be solved in practice.

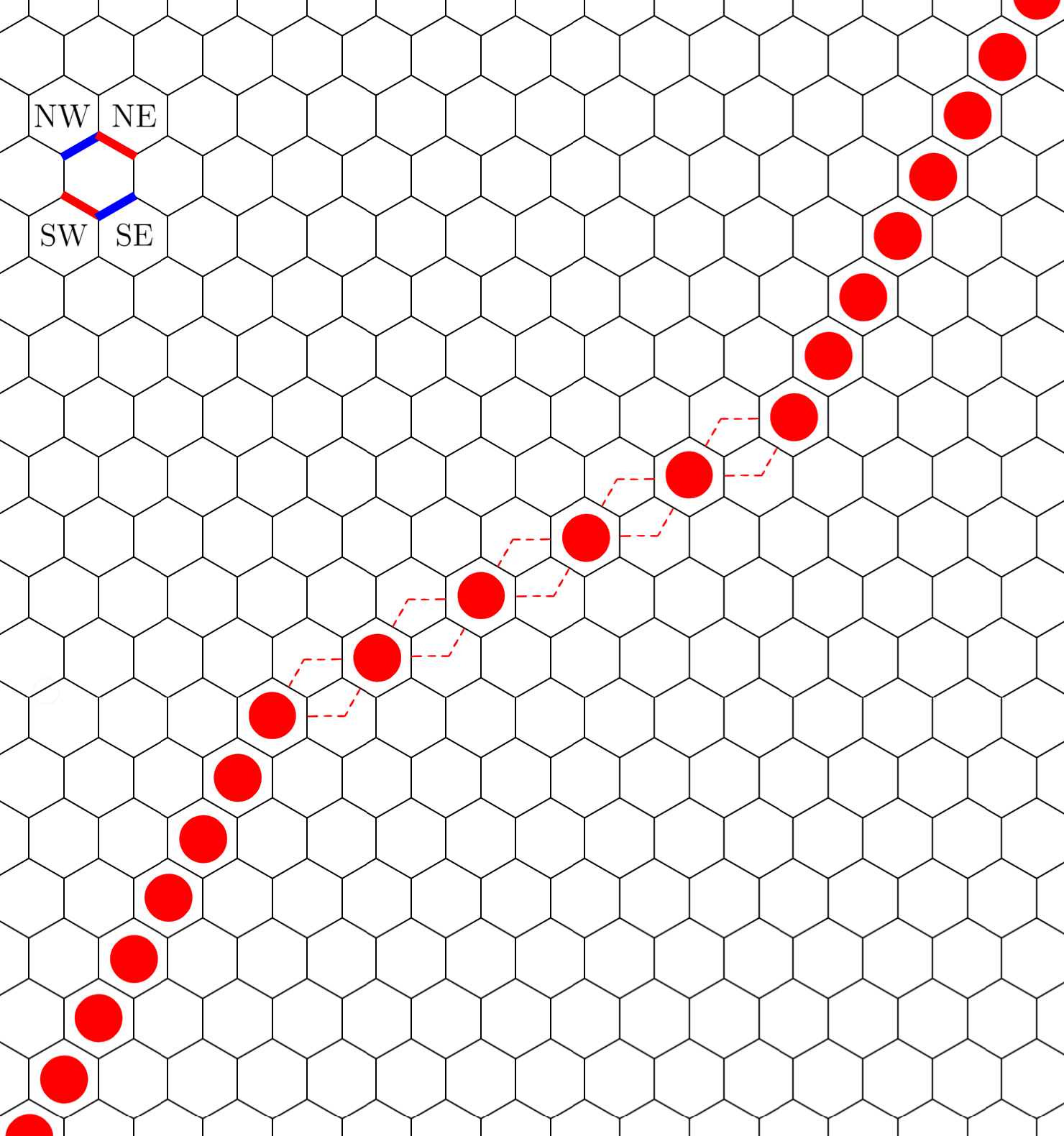

Another observation was that the candidates overwhelmingly chose red as their color, whenever they mentioned a specific color. About 2/3 or more did so. Far behind this was blue, in second place, and then we had a very small number of mentions of orange, green, yellow, and black.

I really enjoyed using this puzzle for the interviews, and I feel it helped us to choose a really great incoming class.

Art by Erin Carmody.